Nancy Sadka, La Trobe University and Josephine Barbaro, La Trobe University

Ahead of the release of the government’s review into the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), the topic taking centre stage is the diagnosis of autism. Over one third of people accessing the scheme list it as a primary disability.

NDIS Minister Bill Shorten has flagged changes to NDIS access, shifting the emphasis from diagnosis to the real-world impact of autism on learning or participation in society. He’s called for education and health systems to step up and be part of a broader ecosystem of supports.

“We just want to move away from diagnosis writing you into the scheme,” the minister said this week. “Because what [then] happens is everyone gets the diagnosis.”

Is autism “over diagnosed” in Australia due to the NDIS, or is it being better identified?

What the data really shows

Recently reported non-peer reviewed research suggests the NDIS has fuelled Australia’s diagnosis rates to be among the highest in the world at one in 25 children. But the same research reported Japan – with early identification and supports in place since the early 1990s – has similar rates.

It’s useful to look at the peer-reviewed data available. A recent screening study we conducted with 13,511 Victorian children aged one to 3.5 years found one in 31 (3.3%) were autistic. This finding was based on data collected between 2013–18 (before and during the rollout of the NDIS).

The United Kingdom reports a prevalence rate of one in 34, based on 2000–2018 data for 10- to 14-year-olds.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report a 2020 prevalence rate of one in 36 children aged eight.

Before the full nationwide rollout of the NDIS, 2020 research based on the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children showed a prevalence rate of one in 23 (4.4%) in 12- to 13-year-olds – even higher than the recently reported paper claiming NDIS was driving up autism diagnosis rates.

We’re getting better at identification

The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children also shows younger children (born 2003–04) have a higher autism prevalence (4.4%) than older children (2.6%; born between 1999–2000). Yet, younger children had fewer social, emotional and behaviour challenges than older children. These findings tell us we are getting better at identifying children with more subtle traits at earlier ages. This is leading to better outcomes.

There is growing awareness of the presentation of autistic people (particularly girls, woman and gender-diverse people) who have historically missed out on diagnosis in childhood due to a lack of understanding of their “internalised” presentation, leading to “masking” and “camouflaging” their differences. They may do this until the demands of life exceed their capacity to cope, leading them to seek a diagnosis.

This has contributed to the overall percentage of autistic participants accessing the NDIS.

Diagnostic overshadowing

Another reason for the rise of autism diagnosis is a phenomenon known as “diagnostic overshadowing”. This is a tendency to explain all differences in a person based on their primary diagnosis.

In the past, many autistic people were diagnosed only with intellectual disability, or misdiagnosed with intellectual disability. As knowledge of autism has improved, more people were correctly diagnosed as autistic, or as both autistic and having an intellectual disability. The result? A clear change in prevalence rates of these two disabilities.

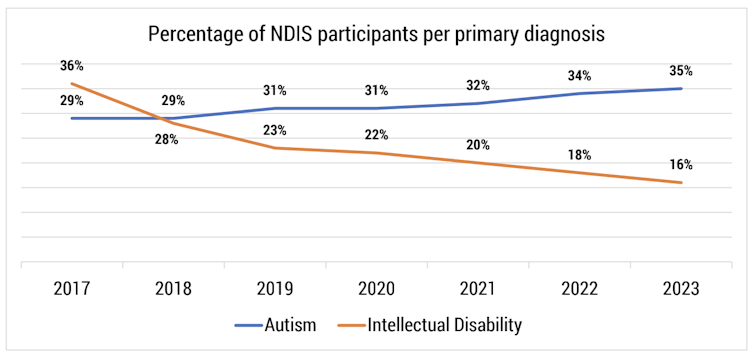

A US study conducted between 2000 and 2014 found the trend of autism diagnosis was on the rise, while the diagnosis of intellectual disability had declined. If prevalence of autism was truly on the rise, rates of intellectual disability would remain static as rates of autism rose.

We see a similar trend of people accessing the NDIS between 2017 and 2023 based on NDIS data. Autistic participants rose by 6% (29% to 35%) from 2017 to 2023, while participants with intellectual disability dropped by 20% (36% to 16%).

This suggests we are not only correctly diagnosing autism as the primary disability, but we may also be reducing co-occuring disability that can significantly impact day-to-day life. This functional focus was the original intention of the NDIS and the purpose Shorten and NDIS review co-chairs have said they want to return to.

A diagnostic ticket to the NDIS

Current eligibility to access the NDIS is based on permanent disability, which substantially impacts the individual’s everyday activity. (Children from birth to nine years old with any developmental concerns or differences can access the Early Childhood Approach, an arm of the NDIS based on needs not diagnosis.)

The National Disability Insurance Agency (the NDIA, which administers the scheme) currently interprets “severity” levels for autism from the diagnostic manual to determine funding. Severity levels range from “requires support” (level one), to “requires very substantial support” (level three). But the diagnostic manual used by clinicians says:

[…] descriptive severity categories should not be used to determine eligibility for and provision of services; these can only be developed at an individual level and through discussion of personal priorities and targets.

This means NDIA eligibility criteria for the scheme excludes needed, meaningful, support for children receiving “level one” diagnoses.

As a result, some clinicians have been accused of “manufacturing” level two diagnosis and “rorting of the system” to ensure NDIS eligibility.

Challenges change over time

NDIS access and funding should not be based on diagnostic levels; it must be based on individual needs. To make the fundamental shift Shorten and the NDIS review co-chairs are foreshadowing, access to the NDIS should not be deficits based. The NDIA will need to educate and train its staff in a holistic approach, focusing on what autistic people can achieve with appropriate supports in place.

If we invest in early supports, autistic children are less likely to require as many supports as they age. This is a good thing for the financial sustainability of the NDIS, which was designed as an insurance scheme and not a welfare system.

Australia is at the forefront of identifying autism early, consequently improving children’s and families’ quality of life. Our rates of early diagnosis should be celebrated, not demonised.![]()

Nancy Sadka, Research Fellow, Olga Tennison Autism Research Centre, La Trobe University and Josephine Barbaro, Associate Professor, Principal Research Fellow, Psychologist, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.