David Trembath, Griffith University; Andrew Whitehouse, University of Western Australia; Hannah Waddington, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington, and Kandice Varcin, Griffith University

Every parent wants the best for their child on the autism spectrum, but navigating the maze of interventions can be tiring, costly and confusing.

The challenge became a lot easier, we hope, with the release of our new landmark report summarising the best evidence for some 111 different intervention approaches.

Prepared by a diverse team of researchers and published by the Cooperative Research Centre for Living with Autism (Autism CRC), the report explains the different types of interventions, which are organised into nine categories.

It also outlines which interventions are well supported by evidence and which are not.

Autism affects the way people understand other people and the world around them. It is a neurodevelopmental condition that can have a major impact on children’s ability to learn and participate in everyday situations. But, most importantly, autism affects different children in different ways.

Early intervention matters. For children on the autism spectrum, effective intervention during childhood is important for promoting their learning and participation in everyday activities.

Read more: It's 25 years since we redefined autism – here's what we've learnt

A bewildering array of interventions

There is a huge variety of autism interventions to choose from, including many with a sound evidence base.

However, the range can be overwhelming, and families risk inadvertently accessing a non-evidence-based, ineffective or harmful intervention if not properly supported to make informed decisions.

Many parents and researchers have likened the bewildering range of interventions to a maze that’s nearly impossible to navigate.

Our report is like a compass that can help guide parents through this confusing labyrinth.

The range of interventions out there can be overwhelming. Shutterstock

What we did

We organised the dizzying range of interventions out there into nine categories. Categorising them this way can help parents, clinicians and policy makers find a common language.

The nine categories are:

- behavioural interventions (such as Early Intensive Behavioural Intervention)

- developmental interventions (such as Paediatric Autism Communication Therapy)

- naturalistic developmental and behavioural interventions (such as Early Start Denver Model)

- sensory-based interventions (such as Ayres Sensory Integration®, or sensory “diets”)

- technology-based interventions (such as apps or gaming-style interventions);

- animal-assisted interventions

- cognitive behaviour therapy

- Treatment and Education of Autistic and related Communication-handicapped Children (the TEACCH program) and

- other interventions that do not fit in these categories.

Our report noted many interventions focused almost entirely on skill development, whereas quality of life outcomes were rarely assessed. Shutterstock

Across these intervention categories, we looked at the evidence on at least 111 intervention practices.

We conducted an umbrella review, otherwise known as a “review of reviews”, which summarises the findings of a decade of non-pharmacological intervention (meaning no medications were used) research involving children on the autism spectrum and their families.

The umbrella review included 58 systematic reviews, drawing on 1,787 unique scholarly articles.

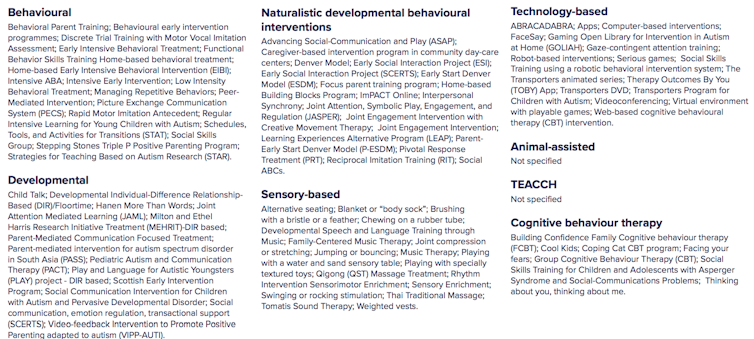

The full list of interventions covered in our “review of reviews” is summarised in the image below, which also shows which of the nine categories each intervention falls under.

Combined practices for each category. Autism CRC

What we found

We found evidence for a number of interventions, and for a range of child and family outcomes. For example, behavioural interventions, developmental interventions, and naturalistic developmental and behavioural interventions all have evidence for improving social communication outcomes in children. These are key skills that help children initiate and maintain conversations with other people.

But for some interventions, the evidence was not strong. For example, TEAACH and certain sensory-based interventions (sensory “diets”) had no supporting evidence that they have a positive effect on child development.

Many assume providing a child with more intervention is better. However, the report found little evidence to support this assumption. It is likely there is a minimum and maximum amount of intervention at which a positive effect is observed (but we don’t know for sure).

We also noted interventions focused almost entirely on skill development, whereas quality of life outcomes were rarely assessed. This should be an issue of major concern for families, researchers and policy makers alike, because, clearly, if an intervention has negative long-term consequences on the child’s quality of life, it’s not something families would want their child to experience.

We have published plain language summary of our findings here.

You can see a table here showing:

- which interventions were supported by evidence from a high quality review

- which had evidence from a moderate quality review

- which had evidence from a low quality review and

- which had no evidence at all from the reviews we looked at.

Many assume providing a child with more intervention is better but there’s little evidence to support this idea. Shutterstock

There are no easy answers. At this stage, the research evidence can’t tell parents and clinicians exactly the right amount of intervention, whether should be delivered one-on-one or where it should happen.

However, we did find evidence programs are often as effective, if not more, when parents are directly involved.

It’s not just about research evidence

Our report examined the evidence (or lack thereof) behind certain interventions, but applying it to individual children and families requires a tailored approach.

To find what’s most effective for your child and family, you’ll need to combine the best available research evidence with the experience and training of the clinician, and the preferences and priorities of the child and their family.

The report found evidence programs are often as effective, if not more, when parents are directly involved. Shutterstock

This where clinical guidelines come in, such as those recently published for how to conduct diagnostic assessments for individuals on the autism spectrum in Australia.

Guidelines take the best available evidence, and combine this with the perspectives of all relevant stakeholders — most importantly, people on the spectrum themselves.

The report provides the research evidence, but finding our way out of the maze for good relies on bringing together a range of views.

Read more: Treating suspected autism at 12 months of age improves children's language skills

David Trembath, Associate Professor, Menzies Health Institute Queensland, Griffith University; Andrew Whitehouse, Bennett Chair of Autism, Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia; Hannah Waddington, Lecturer in Educational Psychology, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington, and Kandice Varcin, Research fellow, Griffith University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.