Bob Buckley

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released new information about autistic people in Australia. The information comes from data collect for the Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) in 2015.

The ABS reports

In 2015 there were 164,000 Australians with autism, a 42.1% increase from the 115,400 with the condition in 2012.

The increase is substantial though it is less significant than previous increases: there was a 79% increase in autistic Australians from 2009 to 2012.

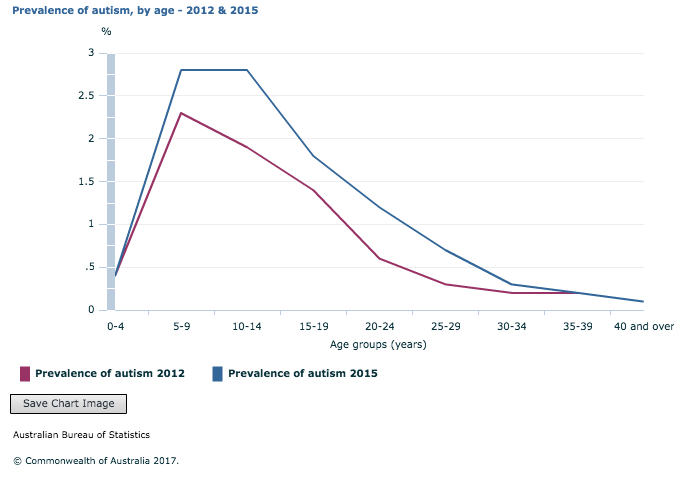

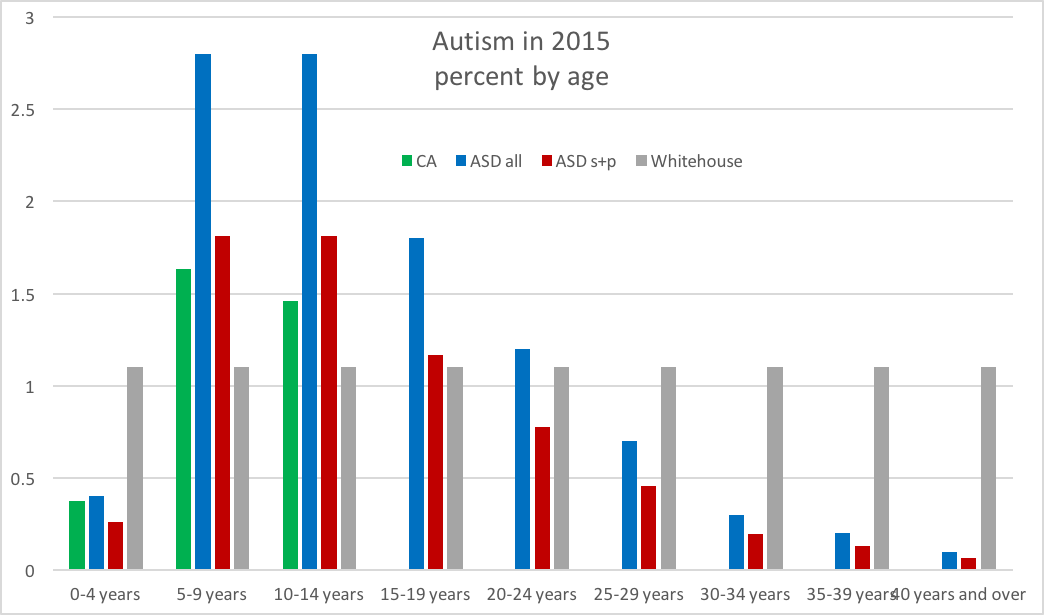

The diagnosis rate for autism spectrum disorder in these (and other) data varies substantially with age. The ABS shows the following figure.

The highest rates of ASD are in children aged 5 to 19 years.

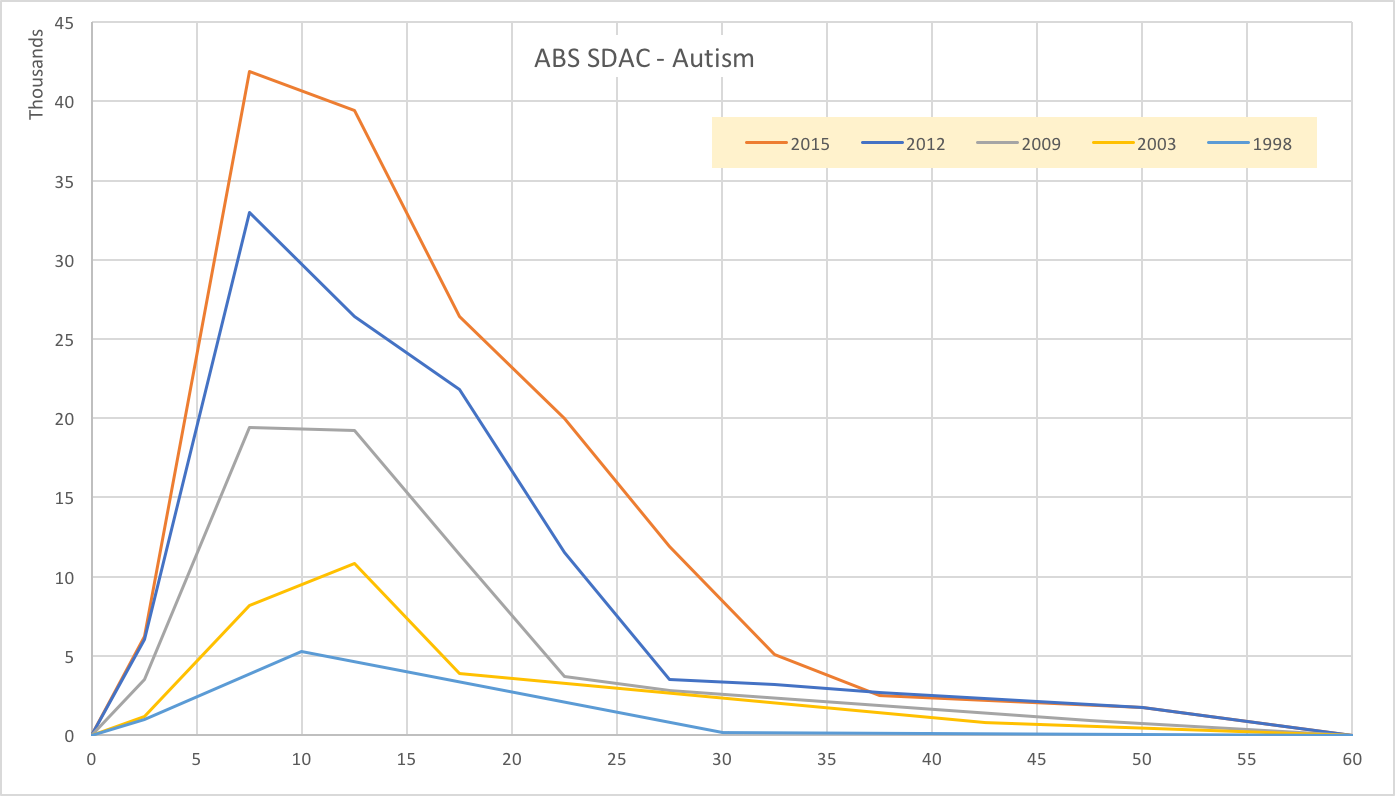

A4 used data from more of the previous SDAC datasets for this graph.

Notable features of these ASD numbers are:

- There are far more autistic young people (under 25 years old) observed than there are autistic adults.

- Since 2009, there are more autistic children in the 5-10 year age range than at any other age.

- Autistic people, once they are diagnosed, apparently remain autistic (so autistic children aged 5-10 years be autistic adults in the future).

- The diagnosis rate for children under 5 years of age may not have increased much from 2012 to 2015 (though these are small numbers so they may be subject to survey sampling error).

The large difference in diagnosis rates between under 30s and over 40s makes describing/reporting of an overall prevalence inappropriate. Observed prevalence of ASD varies enormously with age.

These data indicate there were just 6,200 children aged 0-4 years who were diagnosed with autism in 2015. This is a tiny increase, just 3⅓%, from 6,000 in 2012; it is well below the 42.1% increase observed overall. Note: the precise figures may not be accurate because the diagnosis rate for young children is so low that it has a high margin of error in the survey results. The AMA is concerned by the low ASD diagnosis rate and hopes to improve ASD diagnoses in young children (see https://ama.com.au/position-statement/autism-spectrum-disorder-2016).

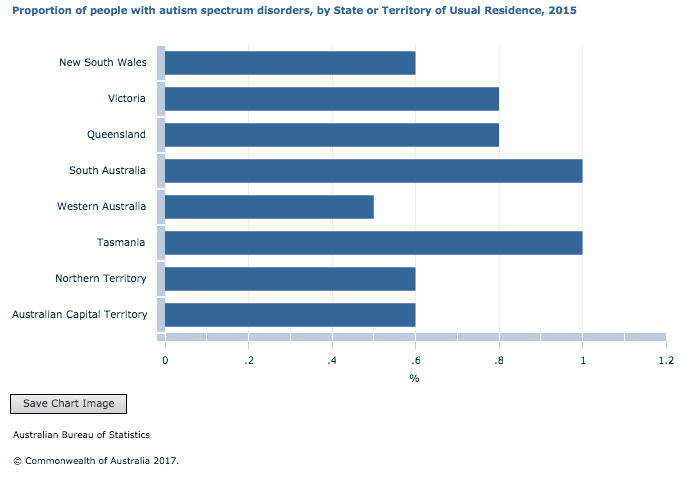

The ABS describes the varied rate of ASD in different Australian states and territories.

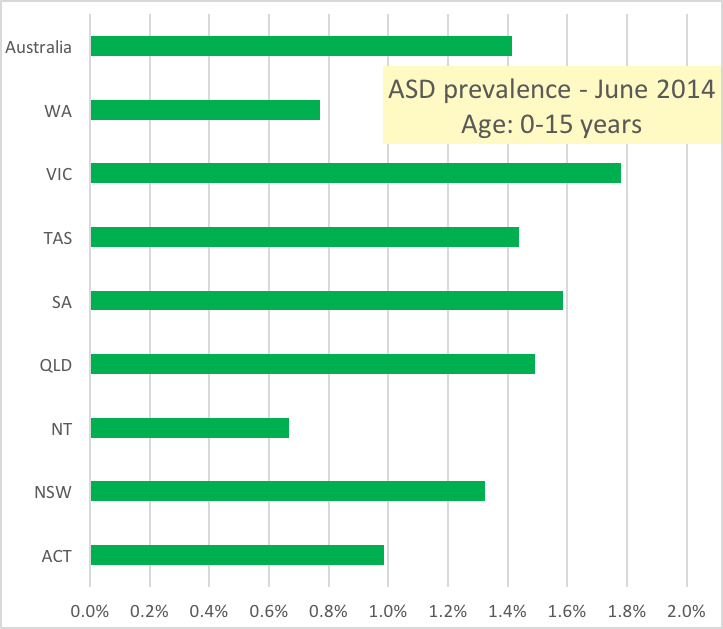

A4 previously produced a similar comparison based on a Centrelink Carer Allowance (child) dataset from 2014 for children under 16 years of age.

Comparison between these two datasets suggests that families in the Northern Territory may have difficulty registering autistic children with Centrelink for Carer Allowance (child).

Primary and secondary education outcomes for autistic people remain particularly poor.

In 2015, almost all children on the autism spectrum had some form of educational restriction (96.7%), including a small number who were unable to attend school because of their disability. Almost half (48.0%) the children attended a special class in a mainstream school or a special school.

and

Of the young people (aged 5 to 20 years) with autism who were attending school or another educational institution, 83.7% reported experiencing difficulty at their place of learning. Of those experiencing difficulties, the main problems encountered were fitting in socially (63.0%), learning difficulties (60.2%) and communication difficulties (51.1%).

Tertiary education outcomes are also abysmal.

People with autism are less likely than others to complete an educational qualification beyond school and have needs for support that differ from people with other disabilities. People with other disability were 2.3 times more likely to have a bachelor degree or higher than people with autism, while people with no disability were 4.4 times more likely to have one.

Education outcomes flow on to employment outcomes. The survey results show that autistic people have especially poor outcomes in employment.

The labour force participation rate was 40.8% among the 75,200 people of working age (15-64 years), living with autism spectrum disorders. This is compared with 53.4% of working age people with disability and 83.2% of people without disability.

The unemployment rate for people with autism spectrum disorders was 31.6%, more than three times the rate for people with disability (10.0%) and almost six times the rate of people without disability (5.3%).

The labour force participation outcomes for autistic people got a bit worse; in 2012, labour force participation of autistic people was 42%.

Most autistic people have severe or profound disability. The ABS reports …

Among people with autism, 64.8% reported having a profound or severe core activity limitation, that is, they need help or supervision with at least one of the following three activities: communication, self-care and mobility.

The rate of severe or profound disability reported for autistic Australian has changed over time.

|

2003 |

2009 |

2012 |

2015 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

87% |

74% |

73% |

64.8% |

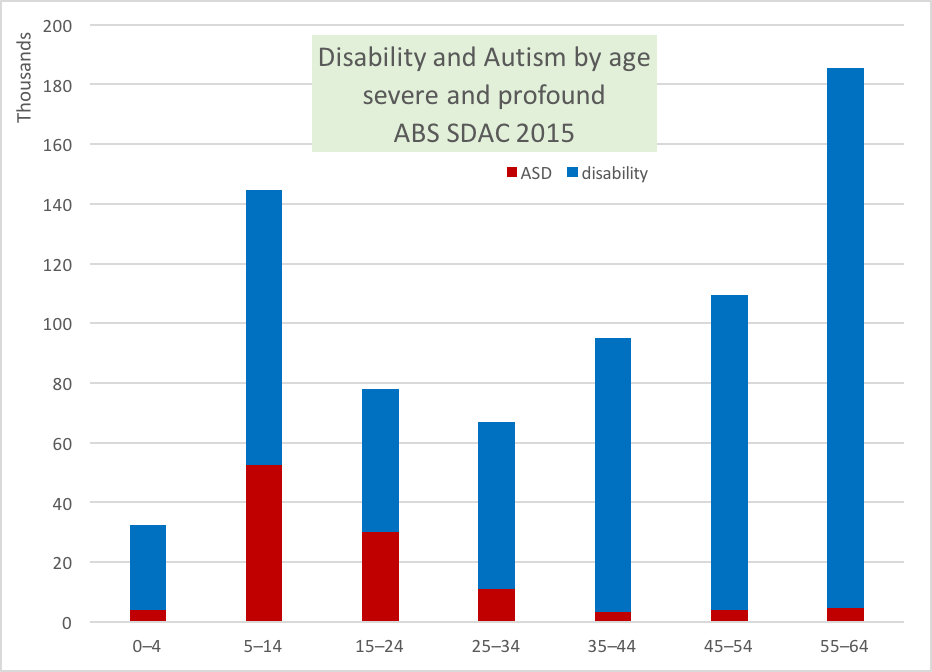

The following figure shows the number of severely or profoundly autistic people and people with severe or profound disability.

The number of autistic people drops off markedly over age 35 years, while the number of people with disability increases.

The following table shows the fraction of autistic people with severe or profound disability compared to people with severe or profound disability generally.

|

Age in years |

ASD/disability |

|---|---|

|

0–4 |

12.4% |

|

5–14 |

36.4% |

|

15–24 |

38.6% |

|

25–34 |

16.4% |

|

35–44 |

3.4% |

|

45–54 |

3.6% |

|

55–64 |

2.5% |

A4 bases much of its prevalence reporting on Carer Allowance (child) data which give detailed population data for autistic children under 16 years of age. The following figure combines data for autistic people from Centrelink’s Carer Allowance (child) data (which is for children under 16 years of age), from ABS SDAC data – all and severe & profound – and Prof. Whitehouse’s claimed 1.1% uniform prevalence for ASD.

Carer Allowance (child) rates are similar to ABS SDAC for severe or profound autism.

Note that if ASD prevalence is really 1.1% of people (as some researchers suggest), then these ABS survey results indicate that there is massive and increasing over-diagnosis of ASD in Australian children. In fact, clinicians would be making wrong diagnoses more often (for 1.8% of children) than they make correct ASD diagnoses (1.1% of children if they don't miss any). At the same time, clinicians would be massively under-diagnosing ASD in adults. These researchers reported previously that they found very little prospect for over-diagnosis (and based on their data A4 observed that over-diagnosis [may happen] in a fraction of cases diagnosed by just 2% of diagnosing clinicians, see Government not intending its autism over-diagnosis claim). Note also that the new criteria for ASD in the DSM-5 (since 2013) were meant to improve the reliability of ASD diagnoses. The DSM-5 criteria may have contributed to the slower rise in ASD diagnosis numbers reported by the ABS in 2012-15 compared to increases in previous survey intervals.

Some of the concerns arising from these data are:

- Increasing diagnosis of ASD bring increased risk to the NDIS

- A tiny increase in diagnosis in 0-4 year olds means many autistic children do not access early intervention that would improve substantially their long-term outcomes and benefit the community generally

- Abysmal outcomes for autistic Australians in education continue even when more ASD-related disability is mild or moderate

- employment outcomes for autistic people are getting worse

- autistic people have substantial needs and many of those needs are unmet

see also

- Why a 42 per cent increase in autism diagnoses is no cause for alarm

- A profile of autism in Australia

- Number of Australians being diagnosed with autism on the rise

- Autism in Australia (AIHW, 2017)

- Autism diagnoses in Australia continue to grow in 2016

- Autism prevalence in Australia 2015

- Data highlights state's highest rate of people living with autism