People with autism are more than twice as likely as their peers in the general population to die prematurely1. The finding, published 5 November in the British Journal of Psychiatry, adds to evidence suggesting that gaps in preventive care can cause serious health problems in people with autism.

Previous studies have hinted at premature death among people with autism, but most of them explored mortality risk in small populations and focused on specific causes of death, such as accidental injury or epilepsy. The new study relies on data from more than 27,000 people with autism and 2.7 million controls from the Swedish population. The researchers found that autism increases mortality risk regardless of the underlying cause of death.

“We observed this increased risk of death in all categories that we could analyze — we don’t really know why,” says lead researcher Tatja Hirvikoski, a neurodevelopmental researcher at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden. “It might be that there are shortcomings in healthcare, and we need to increase knowledge of autism in the health services we provide.”

Hirvikoski’s team identified individuals with autism in Sweden’s National Patient Registry, which includes diagnostic information from all hospital psychiatric visits in Sweden. They then looked for those individuals in theCauses of Death Register, which details how each Swedish resident died.

Calculating the risk of death at any age among people with autism and in the general population, they confirmed earlier predictions that people with autism are about 2.5 times more likely to die early.

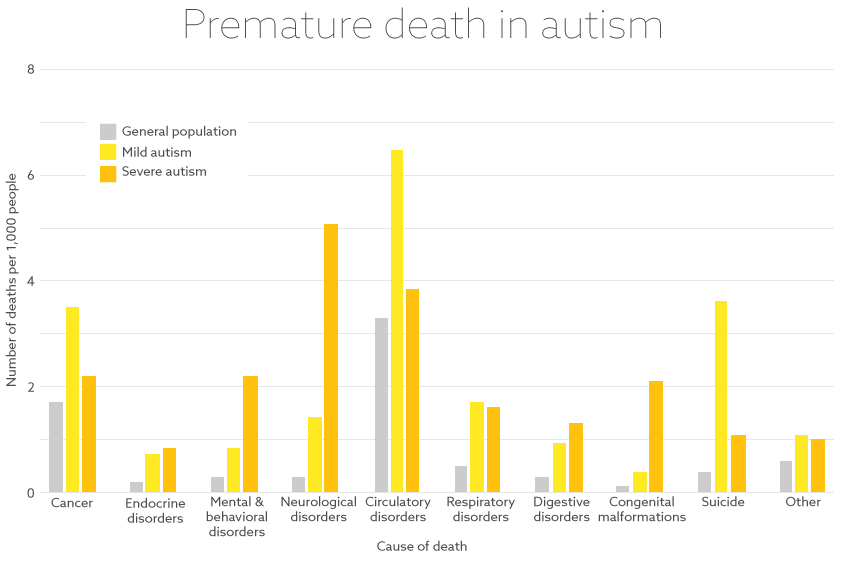

Short shrift: For virtually all causes of death studied, death rates are higher in people with autism than in the general population.

Nigel Hawtin

Suicide risk:

The study’s large sample size allowed the researchers to explore diverse causes of death. The most common cause of death among people with severe autism is epilepsy, which affects roughly 8 percent of people on the spectrum. By contrast, the most likely cause of death among people with mild autism issuicide. The risk of suicide in these individuals is about 10 times higher than in the general population. Women with autism are more likely than men on the spectrum to commit suicide.

These statistics prompted the researchers to revisit a Stockholm clinic’s guidelines for managing depression and suicidal thoughts among individuals with autism.

“We rewrote our local clinical guidelines for the first time in many years,” says Hirvikoski, who also heads research and development for the Swedish government-run clinic Habilitation & Health. She recommended further training for the clinic’s staff.

The researchers also found that mortality rates are higher among people with autism who also have intellectual disability than among those who have autism alone.

They also uncovered gender differences in the causes of death: Women with autism are more likely to die of endocrine disorders such as diabetes or birth defects such as congenital heart malformations, whereas men with autism tend to die because of nervous and circulatory system disorders such as epilepsy or heart disease.

Hirvikoski says she suspects that Swedish healthcare workers overlook calls for help from adults with autism, who may struggle to communicate symptomssuch as pain. Lifestyle factors such as a poor diet, lack of exercise and chronic stress may also contribute to the risk of early death in individuals with autism. These individuals are often overweight or obese, for example.

The researchers are sifting through these factors to determine which ones drive up rates of premature death among people with autism. “Mortality is an extremely serious outcome, so it’s important to look at it in more detail,” says Hirvikoski.

REFERENCES:

- Hirvikoski T. et al. Br. J. Psychiatry Epub ahead of print (2015) PubMed

from https://spectrumnews.org/news/large-swedish-study-ties-autism-to-early-…