The NDIS is a lifeline for four-year-old Eddie’s family. As the number of children being diagnosed grows, experts discuss ways to protect the support for families.

Eight year-old Hugo Hurley doesn’t fit the autism stereotype. “It goes against the common misconception, but he’s a caring, gentle soul, and very loving,” his mother Nicole says. “He’ll tell me 1000 times a day how much he loves me. He kisses me too much and wants to touch me and hold my hand all the time. I’m a hyper-focus for him, which is part of his autism. Also, his relationships are fewer but very deep, which is another part of the obsessive trait in him.” Nicole says Hugo, the elder of her two boys, is also a “walking, talking encyclopaedia on dinosaurs and Pokémon. He’s very sensitive to animals. He wants to be a zookeeper or palaeontologist.”

Nicole’s path into the world of autism was the same anxious, confusing, terrifying and frustrating one faced by so many other parents. “He was born premature at 34 weeks and was in NICU (a neonatal intensive care unit) for a month. In his first year Hugo had problems meeting milestones like rolling, sitting and crawling, but we didn’t really have a frame of reference because he was our first child.”

Initial inquiries with medical practitioners were met with a “let’s-wait-and-see”. They seemed more concerned with whether he was putting on weight as they missed the signs around his development. But at 18 months a psychologist diagnosed Hugo with sensory processing disorder. Again, while he had some therapy for the SPD, and despite its close association with autism, Nicole and her husband were getting pushback in terms of a formal diagnosis. It was suggested they reassess when he reached the age of five.

“But there were more and more signs. He stopped eating and sleeping, and his meltdowns became more intense,” Nicole says. “We were lucky enough to be able to go into the private health system, where a developmental paediatrician told us to start on OT and speech therapy. It wasn’t until Hugo was aged four that we finally received a formal diagnosis of ASD 2 [Autism Spectrum Disorder level 2], along with anxiety, ADHD and insomnia. It was then determined he required substantial supports.”

Nicole estimates it cost around $40-50k in support services in the first year alone before they secured a place on the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS). “We didn’t care, we just wanted to do all we could. And we were lucky because we could afford it. I really worry about what this means for families who can’t.”

Nicole and Hugo’s story will be all too familiar to tens of thousands of families in Australia. The growing prevalence of autism is a hot topic in workplaces, book groups and barbecues across the country. The chatter is backed by the data. Tucked away in the detail of the latest quarterly report of the National Disability Insurance Agency (NDIA) is a statistic that seems impossible to fathom. It tells us that 10 per cent of all boys aged five to seven in Australia are currently on the NDIS, the vast majority due to a diagnosis of autism or developmental delay. For girls of the same age it is one in 25. That’s one in 10 boys in Prep to Year 2 around Australia who have a significant and permanent disability serious enough to be on the NDIS. More than one per classroom. And while the rate of diagnosis among girls is not as high, it is on a steeper trajectory than boys.

There are 83,000 children across the country aged 0-6 on the NDIS, and another 140,000 aged 7-14. More than half (54 per cent) of the scheme’s 266,000 participants aged 18 and under have autism and 20 per cent have developmental delay. They are the fastest-growing category of participants, which now numbers more than 585,000. More than a third (35 per cent) have autism as their primary diagnosis. The NDIS is anticipated to cost the budget $34bn in 2022-23 – including $8.25bn for those with autism as a primary diagnosis, according to new figures from the NDIA – rising to almost $90bn in the next decade. Treasurer Jim Chalmers has called out the NDIS as one of his biggest budgetary concerns.

What is going on? Has it ever been thus, but we just didn’t know? Or is there some new cause for the higher autism prevalence? Why is it different for boys? What does it mean for parents and for the future of the diagnosed child? Given the NDIS is funded by taxpayers, and given the fast-growing numbers of young people in the scheme, how do we pay for it?

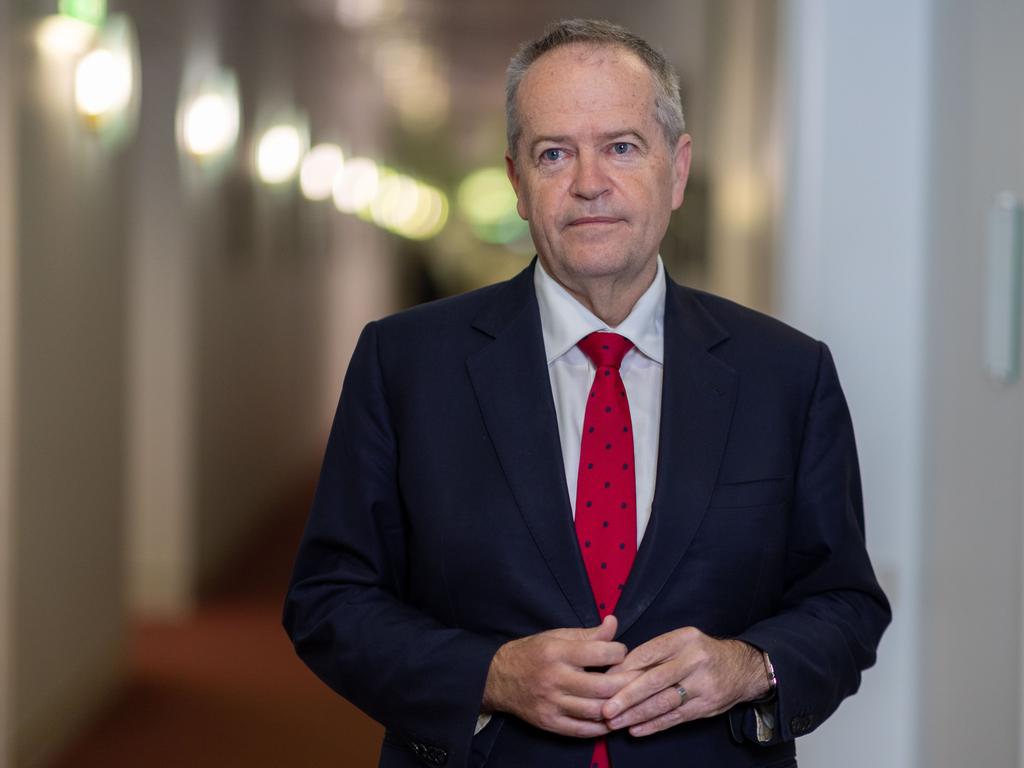

NDIS minister Bill Shorten last year commissioned a review of the scheme, which is due to report in October. The review is examining its design, operations and sustainability, with eligibility understood to be a key focus. Shorten says the NDIS has made a profoundly positive impact on the lives of hundreds of thousands of people with disability, millions when you factor in family and loved ones. But he accepts there is an issue with how many children are finding their way onto the NDIS with an autism diagnosis. “The diagnosis is following the money, so to speak,” he says. “I think what’s happening is that for little kids who might have a learning delay some things are getting badged as autism in order to get them on the path of the NDIS because we don’t have other supports in the broader community.”

The minister says the introduction of the NDIS a decade ago has led to other services previously supplied by state governments and community organisations withering away, leaving the scheme as “the only lifeboat in the ocean” for people with disability.

There are myriad hypotheses about the origins of autism. Premature births. Older fathers. Older mothers. Viruses or bacterial infections during pregnancy. Antidepressants or drug use during pregnancy. Folic acid deficiency. Take your pick. Then there are the wackier theories. The “refrigerator mother” who displays insufficient love for her child, a notion that held sway for much of the 1950s and ‘60s before being debunked. Gut bacteria. The proximity of pregnant women to overhead power lines. Various vaccinations. Paracetamol. A lack of sleep during pregnancy. Exposure to heavy metals, diesel fumes or pesticides. Having a C-section. Too much screen time. Even using a particular position during sex to conceive.

Despite a lifetime of research, the truth is that even now, in 2023, the causes of autism remain opaque. A library’s worth of clinical and academic studies haven’t definitively answered the question. The closest they are prepared to go is that a diagnosis of autism is considered primarily a genetic issue, though no one can completely rule out environmental factors.

Outside the scientific world, it takes far fewer than six degrees of separation to encounter someone navigating Autism Spectrum Disorder. And to have some knowledge of the life-changing impact a diagnosis can have on them and their families.

–

“We understood early there is no magic medicine”

–

Vasily and Margarita Shchegolev are still early in their four-year-old son Eddie’s autism journey. Their victories are small, but also huge. His first word – “more”, his first invitation to a kid’s party. Markers along the path to Eddie’s best life. For more than a year after Eddie was born all seemed OK, normal infant development milestones navigated. But at 16 months Vasily and Margarita started seeing worrying signs. “Eddie stopped responding to his name. He started aligning his toys in a row and pressing the same button on a musical toy for hours,” Vasily says. “He stopped pointing at things and would use his mother’s hand to point or reach what he wanted. He was able to say some words, but then suddenly forgot them. Now we know those were the red flags of autism, but back then we thought it was his way of developing and some quirks. We did go to the GP with some concerns, however we were assured he was too young to have a conclusive diagnosis. We were told he was just a boy and boys develop slower than girls.”

Vasily says a light went on when he watched a TV show where former rugby league and union great Mat Rogers spoke about his experience with his son’s autism and realised Eddie’s behaviours were strikingly similar. Eddie was finally diagnosed at age two-and-a-half as having Autism Spectrum Disorder, and despite all the signs being there it was a tough moment.

“This is the hardest part for most of the parents – to face their child’s diagnosis. Margarita spent weeks in denial, trying to convince me and others that he would grow out of it. When the diagnosis came we felt like all parents in the same boat, alone and grieving. My message to parents like us is to get through those seven stages of grief and reach ‘acceptance’ as soon as possible, because then you’ll start to work out what best to do for your child.”

Vasily jumped on it. “We understood early there is no magic medicine, so we concentrated on evidence-based therapies, speech and occupational and ESDM [a play-based behavioural approach]. It became a case of how we could get access to those therapies and what it would cost.”

The couple spent their house deposit on therapies before Eddie secured an NDIS package. He now receives funding for six to seven hours of early intervention per week, speech, physio, OT and ESDM, and goes to kindergarten two days a week. The average hourly rate for therapists is about $200, and the Shchegolevs are seeing progress. “When after therapy he said his first word ‘more’ and knew what it meant, we were the happiest parents on Earth,” Vasily says. “Another milestone was being invited to the birthday party of a kid in his playgroup. It was a special moment for us when he joined the other kids on the jumping castle and singing happy birthday.”

In attempting to understand autism, the first step is to clarify what we do know. Autism is a condition related to brain development, affecting a person’s ability to communicate, interact and socialise with people. It often involves repetitive behaviours and sensory issues such as over-sensitivity or under-sensitivity to smell, noises or touch, though because it is a spectrum, there are varying symptoms and a range of severity. We know it most often manifests within a child’s first year, though some infants will seem to be developing normally until around 18-24 months when the symptoms first appear. These symptoms often include withdrawal or aggression, loss of language skills and lack of eye contact. Other children may not receive a diagnosis of autism until their school years, or even adulthood. Autism is a disorder, not a disease, and typically lifelong. Early diagnosis and therapy can, however, radically improve the quality of life of those on the spectrum.

Despite being so pervasive, autism has a relatively short history. Austrian-American psychiatrist Leo Kanner is credited with the first formal paper identifying infant autism just 80 years ago in 1943. Kanner highlighted two particular characteristics in the children he observed – severe problems in social interaction and connectedness, and insistence on sameness, which manifested in behaviours such as body rocking and hand flapping. Almost simultaneously in Europe, Austrian psychiatrist Hans Asperger published a new study on boys with a limited range of interests and significant social connection issues, concluding he was looking at a unique form of personality disorder. Both used the term “autistic”.

Studies of identical twins led to a more solid foundation that autism was linked to genetic and biological factors. The disorder was only formally recognised in the bible of psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, in 1980. Through the 1980s and ‘90s autism was still considered a rare, and bleak, disorder. As recently as 1999, studies put prevalence around seven in 10,000 children, the most serious cases. The kids in class who struggled to concentrate, were disruptive or became angry with little provocation were still considered outside formal diagnosis.

Andrew Whitehouse, professor of Autism at the Telethon Kids Institute and the University of Western Australia, says the diagnostic definition of autism in the 1980s and ‘90s was strict in comparison to today. “To be diagnosed, children had to show significant development difficulties, such as ‘gross deficits’ in language development and a ‘pervasive’ lack of responsiveness to other people. This meant they had high support needs, often requiring 24-hour care. Meanwhile, the others were slipping through the cracks. But this changed in the 2000s when autism was reconceptualised into a spectrum, where autistic people didn’t have to also have intellectual or language difficulties to receive a diagnosis,” Whitehouse says.

Gehan Roberts, a paediatrician of 20 years’ standing, has witnessed the change of definition of autism to ASD in his practice. “There used to be a diagnosis called ‘Autistic Disorder’, and then related diagnoses for less severe presentations. Now it is all under the umbrella term ASD, which may include everyone from bright, quirky young people to those with really high needs in terms of personal care, support and even residential accommodation,” Roberts says.

Both experts say the rise in numbers in the past two decades (prevalence rates are now estimated at between one in 70 and one in 100 worldwide) are overwhelmingly due to this change in definition, along with the reduction in stigma and greater understanding by both medical practitioners and the public. “The big change in society, driving an increase in referrals for assessment, is more community awareness and acceptance of neurodiversity,” Roberts says. “And there’s a greater preparedness by families to ask the question early on behalf of their child.”

Whitehouse agrees. “It’s highly likely these children were always there, but not identified or at least identified with another diagnosis. And with greater awareness comes a greater demand to explore the diagnosis.”

There is little argument that genetics is the principal cause, through a genetic difference that has either been inherited or happens by chance. Other factors considered as leaving a child at increased likelihood of autism include being a boy, having a family history (there’s a one-in-five risk of having another child with autism if you already have one) and being born significantly pre-term. Somewhat less clear is having a mother or father of an older age. More controversial are environmental factors floated as having potential associations with autism such as pollutants, medications, screen time for babies, illness during pregnancy and so on. A common one is childhood vaccines, and while many scientific studies including those done by the World Health Organisation have conclusively ruled out a link, the noise persists, perpetuated by anti-vaccination campaigners.

There are differences of expert opinion about how much environmental factors come into play. Adam Guastella, clinical psychologist and University of Sydney professor of child and youth mental health, says that while genetic issues are paramount, more substantial research is looking at possible associations between autism and how genetics and environmental factors could interact to increase vulnerability.

“Teasing apart genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors is really difficult. I don’t think we should be in the business of trying to discount associations between some environmental factors and poorer neurodevelopmental outcomes,” Guastella says. “The older age of parents is brought up, different medications including some that are prescribed, infections during pregnancy. Also drug and alcohol use during pregnancy, serious illnesses in the first trimester of pregnancy, there’s debate about that. The same with traumatic births. It’s an open debate whether they, along with genetics, create some vulnerability and it is important to be considered in response,” he says.

Whitehouse is cautious. “If there was a clear and simple environmental factor that drove a large increase in numbers of people with autism, we would have found it by now,” he says.

Another reason for growing numbers of Australians with autism is greater sophistication around diagnosis of girls. “There is evidence that the way we previously diagnosed autism was more biased toward how boys manifest autism, and was missing autistic behaviours that show up differently in girls. This has seen the ratio fall from around five boys to one girl to around three to one,” Whitehouse says. “An example we often see are girls who are coping at school well, but when they went home their behaviour exploded. This was because they were exhausted at camouflaging their behaviour, and when we looked more closely, we realised that the girls were autistic.

“Another example was the gendered nature of diagnosis. We might have looked at a boy who repeatedly played the same game with cars, but a girl who obsessively lined up her dolls mightn’t have attracted the same scrutiny. We’re simply becoming more aware of the number of kids and families who we need to support.”

Children with autism become adults with autism. Ineka Potma, 21, wants her adult life to start. She wants to leave home and live independently. “She’s into animation and illustration,” her father Paul says. “I see her stuff and say ‘how did you do that?’, and I work in IT.” Ineka provides media content for a disability housing group. “She works 12 hours a week and doesn’t get paid a fortune, but she is stoked to be doing it, even though it’s hard. She wants to do well, she wants to do her own thing and live independently. This is our next challenge.”

Paul says Ineka’s autism was noticeable early on. “You just know it. She has one word when others have 50. At first you get assurances from GPs and paediatricians that it will be OK, but as a parent you know. Eventually we got a diagnosis when she was two and a half. Back then it was a different assessment system, but today it would be called autism spectrum disorder level 2.” He did what others inevitably do: searched for the why. No family history; possibly a traumatic birth; grasping for answers when they aren’t there. “That diagnosis is really a punch in the gut. It was hard for the family.”

Navigating the world of autism pre-NDIS was far harder than it is today. “We kept being told the preschools and local schools were not equipped to deal with her, but on the other hand we were told she wasn’t autistic enough to be given entry to specialist schools,” Paul says. Though even now there are similar issues with finding a job and receiving support.

Pre-NDIS, it was much more expensive. “After they turned seven you got no help at all. We had her in therapies that she was responding to, but I had to pay for everything. I stopped counting when she turned 10 but by then it was about $700k. I don’t regret it because it worked. She started to talk … that’s the return on investment. And it did open her pathways. I can now have a good conversation with her.”

Unpacking the rise in autism prevalence in Australia, as mapped by increasing NDIS numbers, also raises an uncomfortable question. Are children who need extra support to deal with developmental issues being diagnosed with autism as a means to access that support under the scheme? Children are driving the rise in NDIS numbers. Of the 20,500 new participants on the NDIS in the December quarter, 9800 were children younger than seven.

An autism diagnosis often leads to NDIS eligibility. It can be provided by either a specialist multi-disciplinary team or an individual paediatrician, psychiatrist or clinical psychologist. Diagnoses are ranked by severity into three levels. Levels two and three are the more severe levels, which virtually guarantee access to a package of NDIS-funded supports. “If disability systems like the NDIS use diagnosis to determine eligibility then unfortunately we can lead clinical behaviour towards making a diagnosis, even when autism may not be the most accurate or appropriate diagnosis,” Whitehouse says. “It is without question that general clinical behaviour has become biased towards making an autism diagnosis in order to provide families a better chance at receiving support through the NDIS.”

Roberts agrees there is a problem with diagnosis-based funding. “It’s an uncomfortable space. As a clinician seeing someone one on one you want to advocate for what’s best for the child. On the other hand you want a rigorous evidence-based approach where a diagnosis is not made on the basis of enabling access to funding.”

Guastella says the current system is “very diagnosis-oriented”. “At the end of the day the focus shouldn’t be whether a child has autism. Creating the best outcomes for child development should be paramount.”

Chief executive of Autism Awareness Australia Nicole Rogerson, an advocate for people with autism for almost two decades, accepts that something is awry. “Some hard decisions need to be made on eligibility for the NDIS. It shouldn’t be a diagnosis of autism that automatically qualifies you or excludes you from the scheme,” she says. “We need to consider the amount of disability attached to that diagnosis. Some people with autism have significant and severe disability, but some do not.”

–

“The NDIS has made my life so much better. I’m trying my best to live independently”

–

Whitehouse says the current system is contributing to the steep cost trajectory of the NDIS. “Who can blame clinicians or families? If there is a family that requires support, you will do what it takes to get that child support. But it does create sustainability questions about the NDIS. “As a country, we have a finite bucket of money to support an increasing number of vulnerable people. The maths currently isn’t working, and so we have to make hard decisions about how we apportion that money to those who need it the most.” Whitehouse argues that “we need other systems, such as state-based disability and education systems, to reinvest in this area so that children not meeting criteria for NDIS still get the support they need. We should have no child left behind.”

Rogerson is even sharper. “It is absolutely right to say that a lot of this stems back to the states,” she says. “After the NDIS came into being every state backed away from their responsibility for people with disabilities. Education departments deserve extra mention here for their abdication of duty.”

Work is already afoot to support young children with developmental issues outside the NDIS. A program devised by a team led by Whitehouse providing therapy for infants as young as 12 months has been shown to cut the likelihood of a formal diagnosis of autism at age three by two-thirds. Economic modelling of the program suggests that for every 1000 children diverted from the NDIS, the taxpayer would save $75m. And that only takes into account support costs to the NDIS until a child turns 13, not broader economic impacts such as savings to the health and education systems and allowing parents to do more work. Whitehouse says the results have “enormous” implications for children with autism, their families and the financial sustainability of the NDIS.

Despite its issues, the Hurleys, Shchegolevs and Potmas all say the NDIS has made a profound, positive difference to the lives of their children and their families. Vasily and Margarita Shchegolev, an insolvency specialist and a teacher, have both changed careers and started a business providing therapies for autistic children under the age of five. Vasily urges parents not to wait and wonder, and not to be embarrassed. “My wife and I come from a cultural background where disability is taboo, where it would be best to keep your child at home. We’re happy things aren’t the same here. Most important, don’t be afraid to enjoy every moment with your kids. Eddie is a lovely boy, and he’s doing great.”

Ineka Potma’s NDIS package is about $24k a year and includes support such as a psychologist to help her with anxiety. Paul knows Ineka is striving for greater autonomy but suspects he will need to be close by. Ineka says the NDIS has made her life “so much better. I’m trying my best to live independently as an adult with a disability that will hamper me for the rest of my life, but I’m making the effort to do so.”

Nicole Hurley self-manages Hugo’s NDIS package, which costs about $19,000 a year, much less than the average autism package of $41,400. Hugo receives assistive technology supports including orthotics, and capacity building supports including speech therapy, OT, physio and psychology services. She says the family would end up paying about $10,000 more each year out of their own pocket based on what the qualified therapists recommend as his required support. Nicole says it’s hard not to think of the “if onlys”, and notes the system can feel judgmental. “We do wonder if we had a diagnosis at 18 months how much better would his life be now. He missed out on three to four years of therapies.”

Nicole’s advice to parents early in the process is similar to Vasily’s. “Breathe, put your oxygen mask on, and start to work out a plan. It’s OK to grieve, but don’t stay in it too long. You have to get it together.” She recommends a website, Autism: What Next?, which is built by parents, people with autism and leading clinicians. “It’s really good, because otherwise you are left to Google, and that can be scary.” She is optimistic about the life ahead for her eldest son. “Hugo will have a happy and independent life. He wants to travel and has many plans. Funny, but I can really see him as a zookeeper.”