Experts urge early identification and referral for treatment, even if a formal diagnosis has not been confirmed.

In December, the American Academy of Pediatrics put out a new clinical report on autism, an extensive document with an enormous list of references, summarizing 12 years of intense research and clinical activity. During this time, the diagnostic categories changed — Asperger’s syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder, diagnostic categories that once included many children, are no longer used, and we now consider all these children (and adults) to have autism spectrum disorder, or A.S.D.

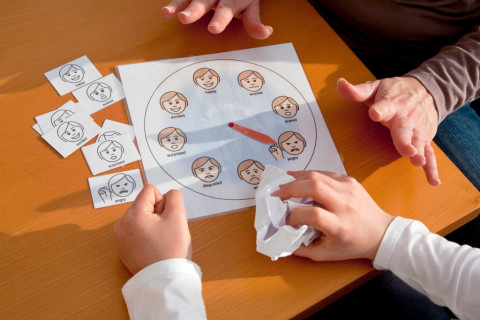

The salient diagnostic characteristics of A.S.D. are persistent problems with social communication, including problems with conversation, with nonverbal communication and social cues, and with relationships, together with restricted repetitive behavior patterns, including repetitive movements, rigid routines, fixated interests and sensory differences.

Dr. Susan Hyman, the lead author on the new report, who is the division chief of developmental and behavioral pediatrics at Golisano Children’s Hospital at the University of Rochester, said in an email that much has changed over the past 12 years. She pointed in particular to increased medical awareness and understanding of conditions that often occur together with A.S.D., and to a greater emphasis on planning — together with families — how to support children as they grow.

Dr. Susan E. Levy, a co-author of the statement who is a developmental behavioral pediatrician at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, said that one key message of the report is the emphasis on early identification and referral for treatment, even if a diagnosis of autism is suspected but not yet confirmed. The outcomes are better when treatment starts as early as possible, she said.

The average age of diagnosis is now around 4 years, but the goal is to get it well under 2, she said. And children who are at higher risk — for example, those whose siblings have A.S.D. — should receive especially close screening and attention.

Since the waits can be long at specialty clinics, the authors of the report hope to see more general pediatricians and primary care providers working with families, even while they are waiting for a full evaluation, referring young children to early intervention or to special preschool programs, so that treatment can begin.

“The interminable wait with worry that parents are faced with currently is untenable,” said Dr. Marilyn Augustyn, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician at Boston Medical Center and professor of pediatrics at Boston University School of Medicine, who also reviewed the new guidelines. “I hope this document makes primary care clinicians more comfortable so while they’re waiting for a diagnosis, they’re doing something.”

And the diagnosis, in turn, may be most important because it can help families access the most effective — and most intensive, and sometimes most expensive — treatments.

What do we mean by treatment? Behavioral interventions are “very, very important,” Dr. Levy said. The most intense intervention is Applied Behavioral Analysis (A.B.A.), a program that addresses specific behaviors, identifying triggers and antecedents, and responding with rewards when a child behaves in the desired way.

There are other behavioral interventions with evidence to support them, Dr. Levy said, and it’s important to start by having a functional behavioral analysis to figure out as much as possible about the particular child and the particular behavior.

“The treatment is behavioral supports and early intervention,” Dr. Augustyn said. “We’re seeing more children learn how to communicate socially,” with behavioral programs like A.B.A., TEACCH, and the Early Start Denver Model, among others.

“There’s a whole host of medical, behavioral and psychiatric conditions that children with autism are more likely to have than the general population, and in some cases can be more disabling than the autism itself,” said Dr. Paul S. Carbone, a professor of pediatrics at the University of Utah, who is the chairman of the A.A.P. autism subcommittee. These conditions affect children’s overall function, he said, and addressing them can really improve quality of life.

Dr. Levy said, “we’re now more tuned in to the fact that children with autism have many co-occurring conditions,” such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, intellectual disability, sleep problems, seizures, anxiety and severe food selectivity. There is also increased awareness of safety issues, especially around “wandering” in children with A.S.D.

These are often children whose communication difficulties can make it hard for them to explain their problems or pains, which can lead to all kinds of behavioral issues. “Plain old constipation I have seen make children so irritable that they engage in aggression toward themselves or others,” Dr. Carbone said.

A child with A.S.D. needs a comprehensive plan, Dr. Levy said, addressing behavioral issues, and educational programming that is appropriate for the child’s strengths and weaknesses. Some children may need occupational therapy for sensory issues; others have language delays.

The first line of treatment for behavioral problems should be behavioral therapies. But when those are not sufficient, medications do come into play. Before medicating a behavioral symptom, it’s again important to understand the behavior as thoroughly as possible. A child could be irritable because of gastroesophageal reflux, or because of an inappropriate educational program.

“There’s no medication that’s going to fix the core symptoms of autism,” Dr. Levy said. But medication may help address some of the concurrent problems, such as A.D.H.D., irritability, anxiety or depression. “Years ago, people felt medication was not effective in kids with autism,” Dr. Levy said. “That’s been debunked.”

Many children with A.S.D. end up taking the medications that are used for A.D.H.D. and for anxiety. Two anti-psychotic medications, aripiprazole and risperidone, are specifically approved for treating aggression or irritability in people with A.S.D. — including children. But the side effects can be concerning, and many practices will start with other medications before resorting to these. If a child is going to take medications like these, “you really want to be working with someone who has good experience and knowledge,” Dr. Carbone said.

The new report also takes into account the research on the etiology of autism, and suggests that it’s worth offering every family the opportunity to look for specific genetic causes, though some families will choose not to have that testing done, and though the knowledge we have now won’t offer clear answers in the majority of cases. “There’s more and more data, and the more we look for, the more we find,” Dr. Levy said.

“I’ve found in my own practice that when we do identify the cause of somebody’s autism, there can be benefits to families,” Dr. Carbone said, because the “diagnostic odyssey” can stop, and parents can feel, “Now I know the cause; how do we move forward?”

And then there is the issue of moving forward out of childhood and into adulthood. Most children with autism grow up into adults with autism, Dr. Levy said, which encompasses a very wide range of levels of function and independence, and of needs for support.

There are some children with “optimal outcomes,” especially those diagnosed very early, she said. But for many families, there will need to be conversations about “working on transition, elementary school to middle school to high school to adulthood,” conversations that may include topics like vocational training and guardianship.

Dr. Hyman pointed to another change over the past 12 years: “The increased awareness of shared decision making that includes the family and individual with autism in planning intervention.”

That means that the conversations with the family — and with the growing adolescent and young adult — should start early to “address transition to adult services related to health, mental health, social skills and employment.”