Imagine starting your first year of school with a volcano inside you. The sound of a ticking fan could overwhelm your senses or the heat from another’s body might stoke its rumbling. Any number of noises or smells can trigger the meltdown of an autistic child who might explode at home if one food touches another on the dinner plate. They might suddenly throw themselves onto the floor, screaming, hitting and kicking out at anyone who tries to restrain them. They might break a window or hurl a chair until an adult removes them, often by force, to a safe place that may be locked and windowless until the chaotic eruption subsides. If the teachers are at their wits’ end they might snap, like the one in Queensland who told a boy to “heel” and then shouted: “Stop being autistic for five minutes!” More likely, the principal will resort to suspension as the cheapest, quickest fix for a problem disrupting schools around the country.

Before he turned six, Thomas McCarthy had been suspended five times from his prep class (the first year of formal schooling) in a Queensland primary school. The fifth landed him home for 10 days. If he’d been away for 11 days, his exasperated mother Mina could have appealed. Instead she poured out her despair in a letter to a Senate inquiry that heard from families of children with disabilities chronicling mostly grim tales of their experience in mainstream school settings. She suspects a dramatic leap in the state’s prep suspensions, from 379 in 2010 to 873 in 2014, confirms the failure to accommodate kids like Thomas. Diagnosed late because of long waiting lists for specialists in regional centres, her son missed out on crucial early interventions. Mina’s passionate cry for smaller classes, better professional expertise in managing autism, more support staff and calming recovery areas for these children captures in a nutshell what a team of Canberra experts took hundreds of pages to recommend after the discovery last year of a “cage” built to restrain an autistic child at an ACT primary school.

Mina, an early childhood teacher with experience in special education who gave up work to advocate for her son, understands both sides of the conundrum. “I understand this behaviour is disruptive and potentially dangerous to staff but there should be strategies in place to identify triggers before they become meltdowns,” she pleads. “I pushed through term one, term two, term three, then I thought, where else can we go?” One day she walked in to find senior staff “kneeling” on her son as his volcano blew. “He was thrashing around, pushing things off the table. He hadn’t de-escalated so the acting principal was holding him down.” Thomas destroyed the tent in the classroom that was meant for his safe withdrawal because others kept using it. After his sixth suspension last October, Mina didn’t return him to the school and has since found a new one. This year she’s praying for miracles.

Suspension, seclusion and restraint in schools stretched by increasing numbers of students with problem behaviours are under scrutiny. Autism now affects one in 100 children. At this rate every third classroom in the country is likely to include a student with Autism Spectrum Disorder, or ASD. Many teachers supervise classes with three or four in the mix, in addition to students who have other issues affecting their behaviour and ability to learn. Victoria’s Mooroolbark East Primary counts 80 children with autism among its 600 students. The principal of a Queensland school where 100 in the population of 500 have disabilities — half with a diagnosis of autism — describes the deep end of “kids hitting, biting, weeing on people, screaming, throwing tantrums, assaulting staff and students, hanging off balconies, swinging a broken broom handle”.

Photographs of the Canberra “cage” built from pool fencing to rein in an autistic child went global on social media last April. Dismantled almost immediately as protests raged, there have since been fresh revelations of windowless rooms and storage spaces operating as “time-out” circuit-breakers. Parents and teachers are at a tipping point. When parents at a Hervey Bay primary school leaked pictures of the darkened room where an autistic child was locked during a meltdown, the Queensland Education Department issued an edict requiring principals to seek parental approval for time-out places.

Such extreme measures point to profound challenges in schools where staff do not have the training, resources or time to manage the kind of personalised learning and supervision these behaviours demand. Veteran disability expert Professor Tony Shaddock concedes the shift of kids with complex behaviours into mainstream schools suffers from flaws similar to those that dogged the 1980s closure of institutions for the mentally ill. “People take a good idea and wreck it by oversimplifying,” he says. “Initially the idea of a teacher’s aide to look after these children was OK, but with lots and lots of kids with a range of disabilities we need to do it differently. What we did 25 years ago doesn’t cut it today.”

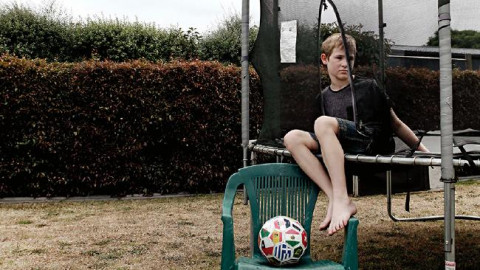

Jack Baulch is bent over a robot computer game as he answers me, his face averted. In one hand he holds a ball of putty that he squeezes and elongates with nervous fingers. “It takes my mind off things,” he says, wrapping the elastic pulp around a big toe. His diagnosis of high functioning autism has been managed with specialist therapies and an aide throughout his primary school years. Good-looking and finely wrought, his face is pinched by a shadow of intensity because social interaction is difficult for children on the spectrum. When I ask him whether he likes school, he doesn’t shy from his demons. “I find it hard to behave. Sometimes I go a bit silly. I start going crazy. I’m not sure why.”

In the comfort and familiarity of home he seems relaxed, but when he returned to school after our visit he became upset, upending children’s drink cans then snatching a boy’s glasses and putting them in a drain. “Just another day dealing with unpredictable behaviour,” says his mother Katrina, who fears for her 12-year-old as he transitions to high school without the support of a government-funded aide. Although a speech pathologist has diagnosed severe language difficulties that put him at risk academically and socially, he falls a straw’s breadth above the cut-off line that determines eligibility.

Katrina rolls her eyes at the rules governing assistance in Victoria. In a letter to education minister James Merlino she describes a recent fairly typical week for Jack at school: “He put another student’s hat down the toilet; wrote inappropriate words on the classroom whiteboard; squashed sandwiches in the toaster to eat melted cheese; called out random words at assembly; lay on the classroom floor screaming and yelling for 20 minutes because he didn’t get his way; sprayed children’s artwork with food dye.” She wrote begging for help as Jack steps up to high school with 15 other autistic children who have also missed out on funding under the state’s Programs for Students with Disabilities.

Funding and services vary from state to state. Some mainstream schools have special education units and there are standalone special schools. But under inclusion policies that dictate that a child should attend a general school wherever possible, some 86 per cent of students with a disability now attend mainstream schools. Schools often shuffle budgets to subsidise aides while parents at private schools can fund their own learning support in classrooms where teachers manage medication, toileting and a complex array of syndromes and disorders requiring personalised attention. One parent with two boys with autism and ADHD says that at least six children in her son’s class of 30 require additional attention. “Because the teacher has limited support not only do the children with additional needs miss out, so does the rest of the class.”

Dark-haired, small and feisty, Katrina Baulch is one of many on the front line who understand the problems difficult children pose for the rest of the class and the staff who are mostly not trained to deal with the meltdowns. Last December she taught a class at Jack’s primary school where an autistic child who is often violent had been confined to a space between two classrooms, spending most days on a computer game. Mindful that this child loves cats, she tried to prepare an activity for him around this theme. “The moment I turned my back he screwed up the paper and threw it away. If I’d pushed him he would have bolted. Later he trashed the room. I didn’t want to send him home because I know his mother is at breaking point.”

Mothers everywhere are on the march. In submissions to the Senate inquiry they speak poignantly of the harrowing road they tread daily. “Our family’s world is small and lonely,” says one. “Most days I’m in tears, wondering at what point exactly do you give your kids up to foster care?” asks a single mother home-schooling a son she says was “suicidal” at six through the distress of trying to navigate school. Others detail episodes of young school-age children holding scissors to their head or threatening injury.

Vanessa Comiskey removed her high functioning autistic son from a school in regional NSW when he began self-harming, scratching his torso until it bled. “I was desperate. I would plant myself in the school front office to be seen because staff were not returning my calls.” At her wits’ end, she took him out of his third school, where he had no special support. Now enrolled in distance education he has thrived, and is set on a career path into air force cadets.

Good news is thin on the ground. “My son has never been to school full-time,” says a mother of an 11-year-old with severe autism and anxiety. Another explains she is home-schooling a son with autism, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive behaviour because his language skills disqualify him from a special school while his disabilities make a mainstream setting impossible. “Unless you have walked the path you cannot comprehend what it is like,” writes Samantha Powell of a son who receives minimal support through a social skills program but no educational aide. “To see your child banging their head against a wall while crying hysterically yet unable to tell you what led to his meltdown … Nobody should have to live through this.”

Parents describe “a Lord of the Flies schoolyard dynamic” where kids are left sitting under desks, kept in corridors, locked into courtyards during lunchtime so they will not harm other children, be bullied or escape onto the road. “My 14-year-old daughter struggles every day to ‘fit in’ and not be punished.” Suspended many times for her meltdowns, the school’s solution was to isolate her. “I have hopes and dreams for her which are possible if someone just cared.”

“Help us,” pleads Robyn Campbell, the mother of two boys with autism. “We struggle every day with children who have no control of their behaviour, thoughts and feelings. The thing about having a special needs child is that you’re always fighting. You’re always exhausted and most of the time you’re just trying to cope.”

Another recounts her son’s first year of school being punctuated with meltdowns, suspensions and escapes until the school reduced his attendance to two hours a day. Just getting him out of the car was fraught. One morning, after tears and physical resistance, she finally shoe-horned him into school where the deputy principal told her he was too upset for class. “I unlocked my car and we got in and went home.” She withdrew him to start again somewhere else.

These are the frustrations that encourage parents to skew diagnoses to procure funding for a teacher’s aide, because without additional one-on-one help their offspring wither. They mortgage homes, sell furniture, anything to pay for therapies not funded by the public purse. Many mothers abandon work to remain on standby when schools summon them because of disruptive behaviour. Success is a lottery that depends on a mix of early diagnosis, robust intervention therapies, a tailored learning plan to modify curriculums, teachers with patience and imagination and principals committed to the noble ideal of inclusion.

The percentage of students with disabilities in primary schools doubled between 1995 and 2006 as anti-discrimination policies funnelled kids into a mainstream setting. The Productivity Commission calculated that 183,610 children with disabilities received funding in 2012, yet that same year figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics reported 295,000 children aged from five to 17 with disabilities were attending schools. Trials of the Nationally Consistent Collection of Data on School Students with Disability returned even higher estimates of 598,824 in 2014. When the autism cohort is extracted from ABS disability surveys the data reveals a 79 per cent increase since 2009 in the number of Australians with this condition, which tags roughly four boys for every girl with the highest prevalence among younger age groups. The reason for this increase is not clear, but would seem to be a combination of more cases and more diagnoses for a condition characterised by problems with social interactions, communication and behaviour.

Disability has ballooned beyond physical or intellectual impairment into an array of psychological conditions. One mother who qualified as a teacher in 2001 says she took a single semester course on children with special needs that focused mainly on visual and hearing impairments. “I can honestly say I was ill-prepared to teach children with special needs,” she admits.

Teacher’s aides were introduced in 1992 initially to provide clerical support. Their role has changed but training and qualifications remain poor. An Australian Education Union survey of staff in 2013 found the vast majority in primary and secondary felt they were lacking the wherewithal to teach students with disabilities. A Queensland principal, who wishes to remain anonymous, says he is desperate to employ staff with special education qualifications. If he can’t find candidates he trains them himself because he believes in catering for this demanding cohort. “Children with autism can’t cope with changes in routines; they can’t filter noise or other sensory triggers that cause them to melt down. They need higher adult ratios, structured regimens and small, safe environments which are sometimes incompatible with mainstream classrooms.” His primary school has seven autistic children who will start secondary level this year without the funding that supported them through childhood. “None of them can function on their own in the mainstream.”

Yet for every complaint of burnout, stress and breakdown among teaching staff there are points of light, places of compassion. Debbie Nelsson, a Victorian principal with almost four decades of teaching experience, is another strong leader committed to ensuring the neediest of her brood at Mooroolbark East Primary are supported, even though only 36 of the 80 students with an autism diagnosis qualify for government help. “It is a ticking time bomb,” she says. “When I started there were not as many kids with difficult issues in the system. Quite a lot of the special schools have closed because mainstream is seen as the best option but the most vulnerable families are not getting the support.”

Like other principals and parents, Nelsson is flummoxed by the number of kids who lose their funding at the end of Year 6 on the cusp of the challenging switch to secondary school. “These kids hate change of that magnitude. We’ve got kids who have improved out of sight during their primary years but they’ll get nothing this year as they start secondary school.”

Nelsson argues that funding in primary settings should continue through the first year of high school and then be reviewed. Listening to her describe carefully thought through strategies for managing meltdowns would be music to the ears of any parent parched of hope. The school has a “sensory” room for children to recover from explosions in the company of an adult. No locks, no blacked-out windows, just a beanbag and quiet music to calm them. “We have a special card that says ‘I’m going to lose it’ which they can show to a teacher,” she explains.

She found funding for two adults to take a child with autism away on school camp. This seems such a meagre gesture until I hear from the parents of a boy who was refused permission for a school trip to Canberra on the grounds of insufficient support staff. His terrible disappointment “led to a meltdown and subsequent suspension” which took his parents to the Human Rights Commission in a case that was dropped after mediation sessions involving lawyers, teachers and hours of argument.

Disability advocate services are mushrooming as parents enlist professional help to resolve disputes and negotiate assistance. Bernadette Beasley taught at a private school in Brisbane before the experience of securing educational support for her child with autism encouraged her to represent others. Melbourne-based advocate Julie Phillips is another “hard-arsed” warrior holding schools responsible for restrictive practices that punish children with autism. “Teachers are supposed to devise positive behaviour plans but they have scarce time, resources or the skills for this so they rely on restraints and seclusion. We have six- and seven-year-olds being suspended or expelled. This cycle is going to worsen until something really bad happens,” she warns.

A support group of parents with autistic children contacts me about a “lock-up” room at a school in regional Victoria that was constructed late last year for the purpose of managing meltdowns. One of the mothers describes a space the size of a disabled toilet. She says matting was laid on the floor after parents complained. “The space is used almost daily because other preventative measures to support these children have not been put in place. The principal’s response was to simply say, ‘We’re not special ed trained’.”

Stephanie Gotlib, CEO of Children With Disability Australia, is receiving more reports of restraints and seclusion. “There is a much higher prevalence of complex kids, not just those with autism, who haven’t benefited from adequate early intervention. These last-resort measures underscore the brutal fact we are not meeting these children’s needs.”

Professor Shaddock, who led the review into Canberra schools after the “cage” controversy, recommends careful monitoring of “withdrawal spaces” to meet human rights obligations. “What really struck me was the high proportion of students in schools with very, very high levels of stress often accompanying a diagnosis of autism. These children find social relationships and new situations extremely difficult so a school setting is a recipe for inappropriate behaviour.” Decades of experience in this field did not prepare him for the “sheer complexity” of nutting out a solution to ensure schools serve “all” children. He discourages cherry-picking demands for teacher’s aides, training and funding in favour of reimagining how schools operate. “Everything in life is becoming more personalised, from laptops to mobile devices, so why not classrooms?”

Seven-year-old Jack Timms is glued to his computer screen but at his mother Pauline’s behest he turns his head towards me with the deliberation of a child who has been taught to make the eye contact autistic children recoil from. Enrolled at a private Melbourne school, he has benefited from parents who can afford to pay $100,000 a year in fees plus therapies plus a full-time aide to ensure he learns according to his needs. Told initially by the school’s principal “we don’t think this is the right school for Jack”, they persevered. “And boy, have we seen the results. But for every couple like us there are 50 who don’t have the backing we have. If I was a single mother on a low income I suspect I would end up like others I know of, home-schooling when their child is expelled for violent behaviour.”

Even with all the resources and support they can furnish there have been problems tailoring classroom rules to dampen his anxiety. Jack hates standing in line, preferring to be in front because of his need to be in control. Pauline explained this quirk to his teacher. “But they kept trying to make him stand in line. Things kept escalating. Jack started scratching children in the line until one day he exploded and smashed two windows before running away. He was off school for three weeks and then restricted to attending for two hours two days a week.”

She recalls Jack tearfully pleading with her one day: “Mummy, can you give me medicine to make my volcano go away so I can go to school like the other kids and not hurt my friends.” She now circulates a letter to parents in her son’s classes explaining his behaviour. “In my time as Jack’s mum I’ve been abused on the street. People have told me, ‘Shut your child up’ or, ‘He just needs a good hiding’. My doors at home are full of stabbing marks and scars from Jack’s meltdowns but these are reducing in frequency and severity because of the skills I’ve acquired along the way.”

Nicole Rogerson, the force behind Autism Awareness Australia, beams proudly when she reveals her autistic son has completed school and now works in hospitality, paying his taxes. “It’s not good saying we want these kids in mainstream schools if we don’t plan for it and we don’t fund it. We send teachers to one day of training and then say, ‘It’s done’. We expel kids or whack them in a room. What message does that send the rest of the class? We have to have a serious national conversation. We can’t throw these kids at the front gate and say, ‘Sort it out’. We need to work together as a community.”

Amid the frustration and discouragement there are currents of hope and pride in children who for all their demons are capable of learning. As the new school year approaches, parents of children with autism will have been preparing for months. “I start agitating in third term for a handover to the new teacher,” one mother explains. “I let staff know about small things that would make a huge difference to my son. I am a constant visible presence. I anticipate situations and triggers to prevent him becoming anxious. I coach the educators. I supply basic aids, such as sensory cushions, pencil grips, fiddle toys. I read between the lines of off-the-cuff comments and sideways looks to find out who is bullying. Even if we are lucky enough to get a competent teacher and aide I can’t just let them get on with the job as I am the only link to my son’s future.”

Parents of children with autism are always on edge, wary of sensory triggers, heeding signs of trouble. This vigilance is strengthening into thorny activism as they lobby governments, politicians, principals and teachers to help them manage the volcanic roar in their midst. Walk in these shoes for the hour it takes to cajole an anxious, disturbed child out of the car or answer the call an hour later to collect them from school and who wouldn’t be shouting for a better way?