These days, the talk is all about neurodoversity, neurodivergence, neuro-affirming stuff. We are told

a neuroaffirming lens ... looking at differences and not deficits.

or

A "neuro-affirming approach" means actively embracing and valuing the differences in how people think and experience the world, particularly those considered "neurodivergent," rather than trying to "fix" or change them to fit a "normal" standard; it recognizes that neurological variations are natural and should be respected as unique strengths, not deficits.

Typically, this is seen as a black-and-white issue. The only options are neuro-affirming (strength-based, deficit-denying) or attempting fixes to make people "normal".

Neither extreme represents autistic diversity.

Just because an autistic (like a dyspraxic or deaf) child does not learn naturally to communicate normally via spoken language does not mean that the child cannot learn to communicate effectively. Once their communication deficit is recognised, recognised and appreciated, most of these children can have their communication deficit fixed by teaching them different communication skills such as AUSLAN, print literacy (reading & writing) or AAC. Some of them may learn spoken language but retain different articulation and ennunciation.

Greater recognition, appreciation, and utilisations of strengths can improve outcomes.

It is unrealistic, even delusional, to expect that all difference and neurodivergence can be seen as strengths, or are entirely positive. Many neuro-divergent people disagree that their neuro-divergence is a super-power; for example see Monique's and Celeste's positions.

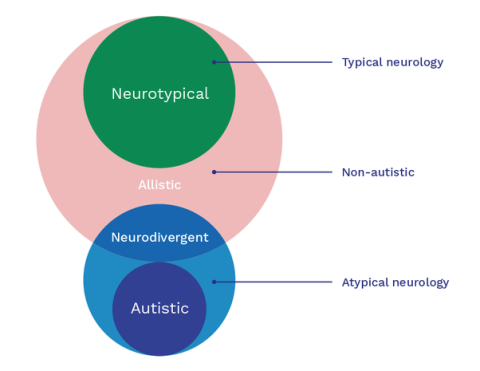

The diagnostic criteria for autism first require that an autistic person needs support in both Part A and Part B of the diagnostic criteria. By definition, and autistic person has impairment that requires support. A person who has only strengths does not have autism; they may well be neuro-divergent but they are not autistic. Still, autism is part of an autistic person's neuro-divergence; not all difference is positive.

Most autistic people have atypical strengths that can be celebrated. But those are neurodivergent strengths, not autism.

Neuro-affirming practices that just ignore impairments and deficits deliver unnecessarily poor outcomes. They result in autistic people, especially children, being denied essential skill development and ongoing supports.

Just because it may be harder to to toilet-train an autistic child does not mean we should affirm pooh-smearing as artistic. Self-injurious or violent behaviour are not autistic super-powers; they cannot be affirmatively reinterpreted as positive personal expression.

Skill development for autistic children, when done properly and ethically, is fun for the child and typiaclly leads to improved independence and well-being.

While it is reasonable for people in the neuro-affirmation movement to decry the extremely bad experiences of people who exerienced some extremely bad practice in the early intervention space, they also need to recognise that some autistic children experienced very positive interventions and supports; good or optimal outcomes are relatively frequent with quality evidence-based therapy. The challenge is it prevent the bad experiences and improve clinical practice that delivers positive outcomes, and especially to ensure that intensive and high-impact treatment is always delivered safely. For example, we do not need the NDIS and its Quality and Safeguards Commission continually promoting high-risk unregulated behaviour support.

Currently, the NDIS legislation does not recognise the triad of impairments that characterise autism, the primary diagnosis for 35%+ of NDIS participants. The National Autism ¾-Strategy and Australia's Disability Strategy 2021-31 Updated omit behaviour support. They don't need to recognise autistic impairment because only neuro-affirming strength-based aspects need be recognised ... and no action is required.

The long-term impact of neuro-affirming autism-denying policy is incalculable.