Donald Grey Triplett was the first person to be diagnosed with autism. The fulfilling life he has led offers an important lesson for today, John Donvan and Caren Zucker write.

After Rain Man, and The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time, the next great autism portrayal the stage or screen might want to consider taking on is the life of one Donald Grey Triplett, an 82-year-old man living today in a small town in the southern United States, who was there at the very beginning, when the story of autism began.

The scholarly paper which first put autism on the map as a recognisable diagnosis listed Donald as "Case 1" among 11 children who - studied by Baltimore psychiatrist Leo Kanner - crystallised for him the idea that he was seeing a kind of disorder not previously listed in the medical textbooks. He called it "infantile autism", which was later shortened to just autism.

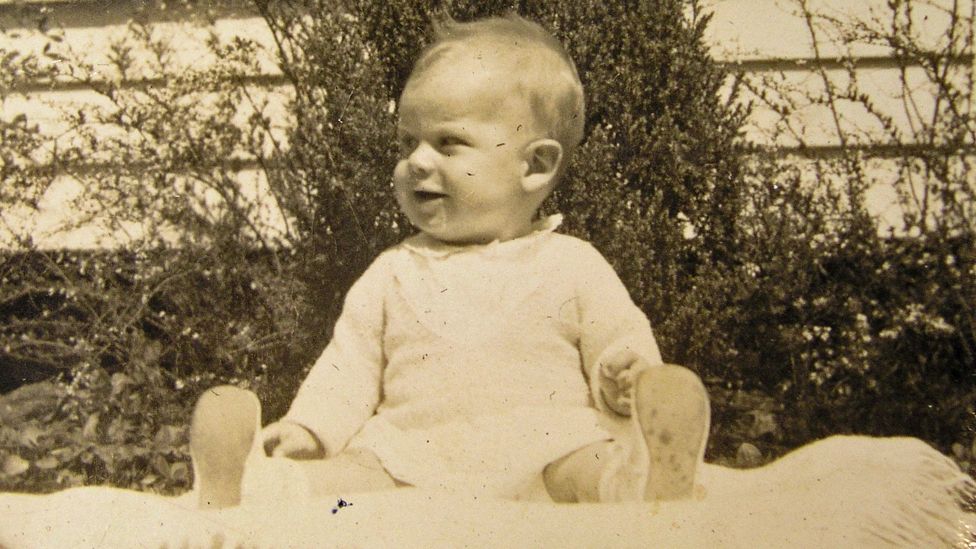

Born in 1933 in Forest, Mississippi, to Beamon and Mary Triplett, a lawyer and a school teacher, Donald was a profoundly withdrawn child, who never met his mother's smile, or answered to her voice, but appeared at all times tuned into a separate world with its own logic, and its own way of using the English language.

Donald could speak and mimic words, but the mimicry appeared to overtake meaning. Most often, he merely echoed what he had heard someone else say. For a time, for example, he went about pronouncing the words "trumpet vine" and "chrysanthemum" over and over, as well as the phrase: "I could put a little comma."

Image copyright Triplett family archives

His parents tried to break through to him, but got nowhere. Donald was not interested in the other children they brought to play with him, and he did not look up when a fully-costumed Santa Claus was brought to surprise him. And yet, they knew he was listening, and intelligent. Two-and-a-half years old at Christmas time, he sang back carols he had heard his mother sing only once, while performing with perfect pitch. His phenomenal memory let him recall the order of a set of beads his father had randomly laced on to a string.

But his intellectual gifts did not save him from being put in an institution. It was the doctors' order. It was always that way, in that era, for children who strayed as far from "normal" as Donald did. The routine prescription for parents was to try to forget the child, and move forward with their lives. In mid-1937, Beamon and Mary complied with the order. Donald, three years old, was sent away. But they did not forget him. They visited monthly, probably debating each time they began the long drive home to Forest whether they should just take him back with them after one of these visits.

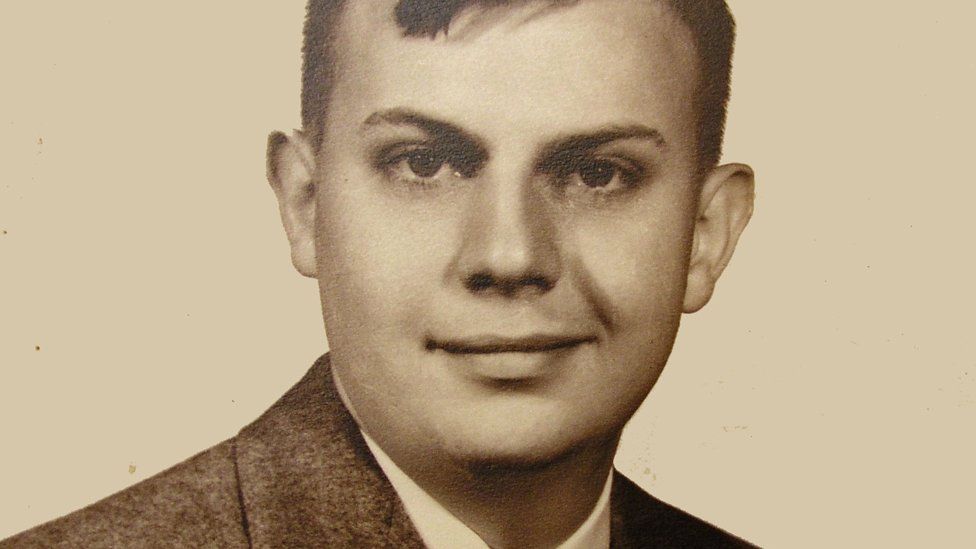

Image copyright Triplett family archives

Image caption Donald's parents refused to let him be brought up in an institution

In late 1938, that is what they did. And that is when they brought him to see Dr Kanner in Baltimore. Kanner was stymied at first. He was not sure what psychiatric "box" to fit Donald into, because none of the ready-made ones seemed to fit. But after several more visits from Donald, and seeing more children with overlapping presentations in behaviour, he published his groundbreaking paper establishing the terms for a new diagnosis.

From there, the history of autism would unfold across decades, playing out in many and varied dramatic episodes, bizarre twists, and star turns, both heroic and villainous, by researchers, educators, activists and autistic people themselves. Donald, however, had no part in this. Instead, after Baltimore, he had gone back to Mississippi, where he spent the rest of his life, unremarked upon.

Image copyright Triplett family archive

Well, not exactly. Donald is still alive today, healthy at 82, and a major figure in our new book. When we first tracked him down, in 2007, we were astonished to learn how his life had turned out.

He lives in his own house (the house he grew up in) within a safe community, where everyone knows him, with friends he sees regularly, a Cadillac to get around in, and a hobby he pursues daily (golf). That's when he is not enjoying his other hobby, travel. Donald, on his own, has travelled all over the United States and to a few dozen countries abroad. He has a closet full of albums packed with photos taken during his journeys.

His is the picture of the perfectly content retiree - not the life sentence in an institution which was nearly his lot - where he surely would have wilted, and never done any of those things. For that, his mother deserves enormous credit. In addition to bringing her boy home, she worked tirelessly to help him connect to the world around him, to give him language, to help him learn to take care of himself.

Something took in all this, because, by the time he was a teenager, Donald was able to attend a regular high school, and then college, where he came out with passing grades in French and mathematics.

Image copyright John Donvan & Caren Zucker

Credit for these outcomes must also go to Donald himself. It was, after all, his innate intelligence and his own capacity for learning which led to this blooming into full potential.

But we saw something else when we went to Forest - and this is where we think the movie of Donald's life would get interesting. The town itself played a part in Donald's excellent outcome - the roughly 3,000 people of Forest, Mississippi, who made a probably unconscious but clear decision in how they were going to treat this strange boy, then man, who lived among them. They decided, in short, to accept him - to count him as "one of their own" and to protect him.

We know this because when we first visited Forest and began asking questions about Donald, at least three people warned us they would track us down and get even if we did anything to hurt Donald. That certainly told us something about how they saw him.

Autism

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a condition that affects social interaction, communication, interests and behaviour

- In children with ASD, the symptoms are present before three years of age, although a diagnosis can sometimes be made after the age of three

- It's estimated that about one in every 100 people in the UK has ASD - more boys are diagnosed with the condition than girls

- There's no "cure" for ASD, but speech and language therapy, occupational therapy, educational support, plus a number of other interventions are available to help children and parents

Sources: SourceNHS Choices - Autism spectrum disorder ; NHS Choices - Living With Autism

In time, however, as we gained more people's trust, more details came out about how, throughout the years, Donald was embraced. His school yearbook is full of scribbled notes from classmates talking about what a great friend he is. A few of the girls even seemed a little sweet on him.

We learned that he got cheered for his part in a school play, that people regarded his obsessive interest in numbers not as odd, but as evidence that he must be some kind of genius. We met a man Donald knew in college, now an ordained minister, who tried to teach him to swim in a nearby river. When that failed, he tried to give Donald lessons in how to speak more fluidly, which was also something of a lost cause.

That is because Donald still has autism. It did not go away. Rather, its power to limit his life was gradually overcome, even though he still has obsessions, and talks rather mechanically, and cannot really hold a conversation beyond one or two rounds of exchanged pleasantries. Even with all that, though, he is a fully fledged personality, a pleasure to hang out with, and a friend.

Image copyright John Donvan & Caren Zucker

Image caption Donald with the authors, John Donvan and Caren Zucker

What Donald's story suggests is that parents hearing for the first time that a child is autistic should understand that, with this particular diagnosis, the die is never cast. Each individual has unique capacity to grow and learn, as Donald did, even if he hit most of his milestones rather later than most people. For example, he learned to drive only in late twenties. But now, the road is still his. Literally.

That is something of a perfect ending. And if the movie of Donald's life gets made, we hope, when the credits roll, that a line on screen will say something like: "The producers would like to thank the town of Forest, Mississippi, for making this story possible." But also, we would like to add, by making all the difference, by doing the right thing.

John Donvan and Caren Zucker are the authors of In A Different Key: The Story of Autism