Study co-authors Wah Chin Boon, left, and Anne-Louise Ponsonby of the Florey Institute. Inset: The effect of plastic chemical bisphenol A on the body, showing decreased spine density (red dots) and shortened neurites. Picture: Nadir Kinani

Boys with lower levels of a key brain enzyme who are born to mothers with higher levels of plastic chemicals in their wombs are six times more likely to develop autism by the time they are a teenager, a world-first Australian study has found.

A decade-long study by the Florey Institute has for the first time established a biological pathway between the plastic chemical bisphenol A (BPA), which is found in food and drink containers, cosmetics and packaging, and autism spectrum disorder.

“BPA can disrupt hormone-controlled male fetal brain development in several ways, including silencing this key enzyme, aromatase, that controls neurohormones and is especially important in fetal male brain development,” study co-author Anne-Louise Ponsonby said. “This appears to be part of the autism puzzle.”

BPA is a chemical that is added to plastics to make them more malleable and durable. It is virtually impossible to avoid in daily life.

Several previous studies have posited a link between it and autism, but the Florey study is the first long-term research incorporate human studies to examine the interplay between prenatal BPA, aromatase function and the development of autism in a large cohort of mothers and babies.

Research finds links between prenatal plastic exposure and autism in boys

The researchers studied 1770 children over 10 years from two cohorts of mothers and children in the Barwon Infant Study in Australia and the Columbia Centre for Children’s Health and Environment in the US, finding that boys in this group who were born to mothers with higher urinary BPA levels in late pregnancy were 3½ times more likely to have autism symptoms by the age of two, and six times more likely to have a verified autism diagnosis by age 11.

“I do want to stress it’s not the cause of autism,” Professor Ponsonby said. “Autism is a multi-factorial disease, and it’s going to have a range of genetic and other drivers. So this is a contributing factor in some cases.”

In the two large birth cohorts studied, it was established that higher BPA levels in pregnant mothers were associated with epigenetic changes, or gene switching which suppressed the aromatase enzyme. As well as establishing the link in humans, Florey scientist and co-author Wah Chin Boon was also able to establish for the first time the biochemical pathway in which BPA suppressed aromatase in laboratory mice studies.

“We found that BPA suppresses the aromatase enzyme and is associated with anatomical, neurological and behavioural changes in the male mice that may be consistent with autism spectrum disorder,” Dr Boon said.

“This is the first time a biological pathway has been identified that might help explain the connection between autism and BPA.”

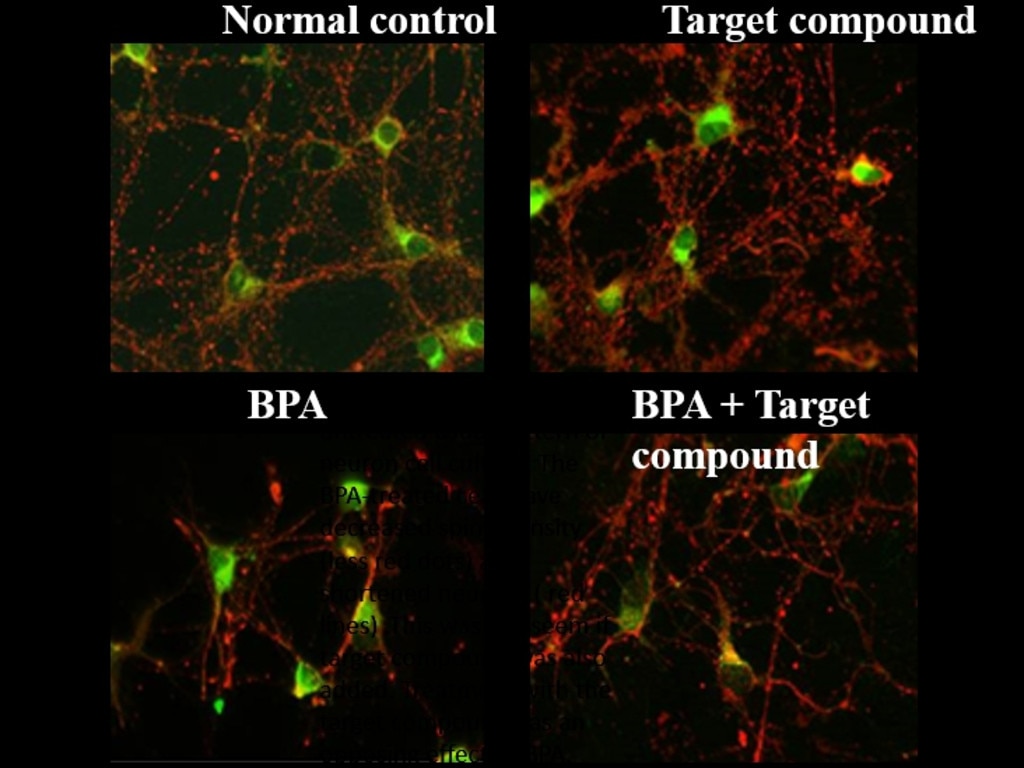

Microscope slides showing how a target compound has an opposing effect on BPA. Top row: left – neuron cell culture with normal cells, with the top left showing a usual pattern of neurons. Top row: right – cells treated with a compound that was the subject of the study. Bottom row: left – cells subjected to BPA showing decreased spine density (red dots) and shortened neurites (red lines). Bottom row: right – This was not seen when the target compound was also added.

Professor Ponsonby said that the findings indicated that among boys in the general population with a greater inherent vulnerability to the effects of endocrine disruptors, about 10 per cent of autism diagnoses may potentially be able to be prevented by BPA avoidance if the BPA -autism link was causal in nature.

Aromatase has been described as “a master controller of steroid hormone-directed brain development” and is responsible in the brain for converting the hormone testosterone to neuroeostrogen.

“Aromatase is more important in male brain development,” Professor Ponsonby said. “These finding may explain some of the male excess observed in autism.”

In lab studies, the Florey has also for the first time identified a possible “antitode” to this process – a type of fatty acid that when injected in mice was found to reverse the disruption of aromatase.

The scientists posited that the fatty substance, which is a major lipid component of the royal jelly of honeybees, may be able to correct a deficiency in aromatase-dependent estrogen signalling in the brain. They say this potential antidote warrants further study.

BPA is a chemical used in the lining of some food and beverage packaging to protect food from contamination and extend shelf life. Small amounts of BPA can migrate into food and beverages from containers. Tiny amounts of the chemical can enter the skin via clothes and cosmetics, and it can also be inhaled in things like paint fumes.

In 2010, the Australian government announced a voluntary phase-out of BPA use in polycarbonate baby bottles.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand recent said that when food safety authorities around the world reviewed BPA “they have generally concluded there are no safety concerns at the levels people are exposed to”.

However, last year the European Food Safety Authority published a re-evaluation of the risks to public health from the presence of BPA in food.

It concluded the tolerable daily intake for BPA should be substantially reduced from the temporary value it had previously established in 2015.

Australia’s regulator says it has “considered EFSA’s re-evaluation of BPA and has reservations about the approach taken”.