British-born author Daniel Tammet corresponded with poet Les Murray, who died on April 29 aged 80, and translated his poems into French. In his 2017 book Every Word is a Bird We Teach to Sing, Tammet describes how Murray’s inspiring example helped him come to terms with being autistic. In this edited extract he recounts how he and Murray came to share a stage in Paris in 2015.

Daniel Tammet

The Australian poet Les Murray makes life hard for those who wish to describe him. It isn't only his work, some 30 books over 50 years. It is the man. In PR terms, Murray seems the antipode of Updikean dapperness, cold Coetzee intensity, Zadie Smith's glamour. His author photographs, which appear to be snapshots, can best be described as ordinary. The bald man's hat, the double chin, the plain T-shirt. A photograph, accompanying his New Selected Poems, shows him at a kitchen table, grandfatherly in his glasses. The artlessness is that of an autodidact. Murray has always written as his own man. Fashions, schools, even the occasional dictionary definition, he serenely flouts. To read him is to know him.

A high hill of photographed sun-shadow

coming up from reverie, the big head

has its eyes on a mid-line, the mouth

slightly open, to breathe or interrupt.

The face's gentle skew to the left

is abetted, or caused, beneath the nose

by a Heidelberg scar, got in an accident.

The hair no longer meets across the head

and the back and sides are clipped ancestrally

Puritan-short. The chins are firm and deep

respectively. In point of freckling

and bare and shaven skin is just over

halfway between childhood ginger

And the nutmeg and plastic death-mottle

of great age. The large ears suggest more

of the soul than the other features:

(These lines are from his Self-Portrait from a Photograph, in Collected Poems.)

His is a singular way with words; Murray admits to interviewers that he is something of a "word freak". His linguistic curiosity is immense, obsessive. Gnamma (an Aboriginal word for desert rock-holes wet with rainwater), the Anglo-Hindi kubberd aur (from the Hindi khabard aar meaning look out!), toradh (Irish Gaelic or fruit or produce), neb (Scots for nose), sadaka (alms in Turkish), the German Leutseligkeit (affability), rzeczpospolita (what Poland, in its red-tape documents, calls itself), halevai (a Yiddish exclamation): these are just a few of the many exotic words which Murray, over the years, has lavished on his poetry.

A newspaper report in 2014 noted Murry lives with high-functioning autism.

I discovered Les Murray in the early 2000s (a short while before my own high-functioning autism diagnosis). It happened in an English bookshop.

Every now and then I came into the shop and thumbed its wares and pretended to have money. In the poetry section one day, I was looking at the stock – short books written by long names like Annette von Droste-Hlilshoff, Guillaume de Saluste Du Bartas, Keorapetse Kgositsile, Wisfawa Szymborska – when a cover that bore the surprisingly modest name of Les Murray caught my eye. The familiarity of that 'Les', its ungentlemanliness, so seemingly out of place in a poetry section, appealed to me. And the book's title was as intriguing as the author's name was likeable: Poems the Size of Photographs. I picked it up and read. And read. It was the first time I read a book from cover while standing in the shop.

Proving the theory wrong

Without Murray's poems, I might never have become a writer. At the time, so early in my adulthood, their oddness reassured. I could see myself in them. In London, my English had never been the English of my parents, siblings, or schoolmates; my sentences – oblique, wordy, allusive – had led to mockery, and the mockery had caused my voice to shrink. But Murray's was sprawling; it held a hard-won ease with how its words behaved. If I had known then what I finally confirmed years later, that this poet's voice, so beautiful and so skilful, was autistic, and that Murray was an autistic savant, I might have seen myself differently. I might have written my essays and my first novel and my own poetry years before they finally made their way into print.

Les Murray at home in Bunyah in 1996. Robert Pearce

Happily, this hunch was enough to restore confidence in my own voice, to nourish it back up to size. My voice eventually grew as big as a book: a memoir of my autistic childhood.

As early as the 1970s Murray wrote, in a poem entitled Portrait of the Autist as a New World Driver of belonging to the “loners, chart-freaks, bush encyclopaedists … we meet gravely as stiff princes, and swap fact”; in several more newspaper profiles, he described himself as a “high-performing Asperger” (a pity, too, I didn't see these at the time).

In the end, it was Murray's The Biplane Houses that turned my hunch to certainty. By that time I had left Kent and its bookshop and was living in the south of France. I ordered my copy in a click of internet: it arrived in a many-stamped airmail envelope – a small, slender, red and white book looking none the worse for the cross-Channel journey. As I flipped through the poems, I read, in the form of a sonnet, not a declaration of love, but the author's contemplation of his mind:

Asperges me hyssopo

the snatch of plainsong went,

Thou sprinklest me with hyssop

was the clerical intent,

not Asparagus with hiccups

and never autistic savant.

Asperger, mais. Asperg is me.

The coin took years to drop:

Lectures instead of chat. The want

of peo ple skills. The need for Rules.

Never towing a line from the Ship of Fools.

The avoided eyes. Great memory.

Horror not seeming to perturb –

Hyssop can be a bitter herb.

I had read in who knows how many scientific papers that people with autism took up language – even 20 varieties – merely to release it as echoes. So I was thrilled to see Murray's lines, full of wit and feeling and prowess, prove their theories wrong. They made me want to learn all about the man behind the pen. I went to my computer; I punched in the poet's name and autism; the resulting web pages were many, well stocked, enlightening. The information had been there all along. But the reporters had pushed it to the margins.

When my debut collection of essays was published several years ago, I dedicated a copy to the poet as a token of gratitude and admiration. But I hesitated before posting it to the bush of New South Wales. What if the book never reached him , or arrived but didn't please him ? For a while I couldn't make up my mind. Finally, though, I let my timidity pass. I wrote to the address I had found for Murray in a literary journal, and several weeks later – restless weeks, since each seemed to me to last a month – I had a letter from him.

Translating Murray wasn't something to be taken lightly. Murray's English is vivid, inventive, jaunty. He is fond of the striking word choice.

— Daniel Tammet

Time and care had been expended on the letter. Murray's penmanship was firm and fluent (I especially liked his a's' neat little pigtails); the letter was quite long. Far more than a simple thanks then, or even some compliments: the tone throughout was expansive, even confiding. I was touched. What touched me most was Murray's request that I write again to keep him abreast of my news and my work. An invitation to correspond.

I took him at his word. I wrote. He wrote back. And so it was that letters later, in the course of our now regular correspondence, I proposed to translate a selection of his poems in to my second language, French.

Trust and generosity

I had a seen a gap in the international literary market: Murray's poetry, in translation, was already on sale in Berlin bookshops, Moscow libraries, Delhi bazaars. But not, for some strange reason, in the city, a cultural capital, that I had begun to call my home: Paris.

The poet's agent agreed; my editor in Paris agreed. And Murray, in his expansive Australian way, gave me a free hand, carte blanche. I reread the poems, collection after collection after collection; for days, weeks, I immersed myself in them; I ended up selecting 40 of my favourites to translate.

Murray in 2009. Peter Rae

Translating Murray, I knew, wasn't something to be taken lightly. Murray's English is vivid, inventive, jaunty. He is fond of the striking word choice.

My translation, C'est une chose serieuse que d'etre parmi les hommes (It is Serious to be with Humans), was published in the autumn of 2014. On October 12, radios tuned into France Culture spoke for 30 minutes in my voice. They told listeners of Murray, his life and work, the repayment of a young writer's debt to his mentor. The broadcast went around the French-speaking world.

Some months later, Murray wrote with pride of a Polynesian neighbour, a native French speaker, who admired the translation and was using it in her French classes. And though his own French was rusty, he said, he could nevertheless understand and enjoy quite a lot,

In other letters and postcards – their news 10 days older for being sent by snail mail (Murray dislikes computers) – he affectionately recounted long-past trips to Britain, Italy, Germany and France. But there was nothing in these messages suggesting he might one day return; he hadn't been back in years. He was well into his 70s; his health was unreliable; his farm in Bunyah was more than 16,000 kilometres away.

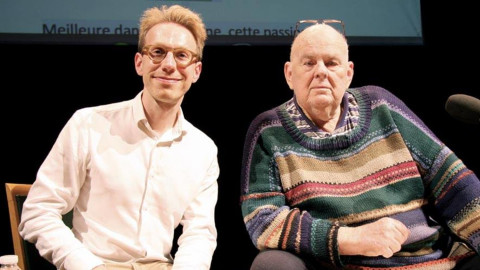

So the news that he would be in Paris in September 2015 came out of the blue. He had accepted a festival's invitation to speak at the Maison de la Poesie. I was thrilled. Honoured, too, when the organiser asked me to share the stage with the poet. Copies of the translation would be on sale after the talk.

Murray, in a multicoloured woolly pullover – a dependable "soup-catcher" – braved the 20-plus hours on an aeroplane and met me in a bistro. To be able to put a voice, so rich and twangy, to the poems after all this. time! At the Maison, the following evening, our conversation had an audience and spotlights, and was interspersed with readings in both languages.

After the event, a book signing. The queue was gratifyingly long. I was backstage when someone from the festival came to fetch me; Murray wanted me to sign the book with him.

Murray said, 'It's only fair. We're co-authors.'

Every Word is a Bird We Teach to Sing by Daniel Tammet (Hodder and Stoughton)

from https://www.afr.com/lifestyle/my-friend-and-mentor-les-murray-autistic-…;