Karen R Fisher, UNSW; Erin Louise Whittle, UNSW, and Julian Norman Trollor, UNSW

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) began a full national rollout in July, 2016 with a fundamental principle to give those with a disability choice and control over their daily lives. Participants can use funds to purchase services that reflect their lifestyle and aspirations. Two years on, how is the scheme faring?

Full implementation of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) started two years ago, but many people with disability are not receiving the support they need. One such group are people with complex support needs, such as people with intellectual disability who also have mental health needs.

Fewer people with complex needs are receiving the NDIS, and those who are using it have worse outcomes than others. Some can’t receive support because the scheme hasn’t yet reached where they live. Others may receive funding, but not be able to use it if there aren’t services in their local area. Others receive NDIS support but the promise of greater choice and control over their support has not yet happened.

What the evidence says

An NDIS package allows people with significant and ongoing disability needs to purchase support. The aim is for people to make their own decisions about the support they need so they can achieve the same things as others in their community.

Read more: The NDIS is delivering 'reasonable and necessary' supports for some, but others are missing out

An independent evaluation of the NDIS conducted by researchers from Flinders University found one-third of NDIS participants couldn’t find the disability support they needed because of a lack of local providers and a lack of quality services. This shortage of suitable services is worse for people with complex needs.

People with intellectual disability experience higher rates of mental ill health than the rest of the population, although the data on exact rates vary depending on the context. Mental illness refers to conditions including depression and anxiety, as well as psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia.

While the number of NDIS providers has nearly doubled since June 2017, this increase also signals a new workforce who need training to support people to get the services they need.

This is especially so when consumers’ needs cross over between the NDIS and other sectors, such as mental health. The NDIS pays for some mental health support, but state and federal governments are responsible for the rest, and shortfalls are common.

People with intellectual disability find it much harder to access mental health support and often don’t receive satisfactory or appropriate treatment. The design and delivery of mental health services and health policy often overlooks the specific needs of people with intellectual disability. These can include needing extra time to build rapport and trust with service employees, using accessible language and working collaboratively with other services.

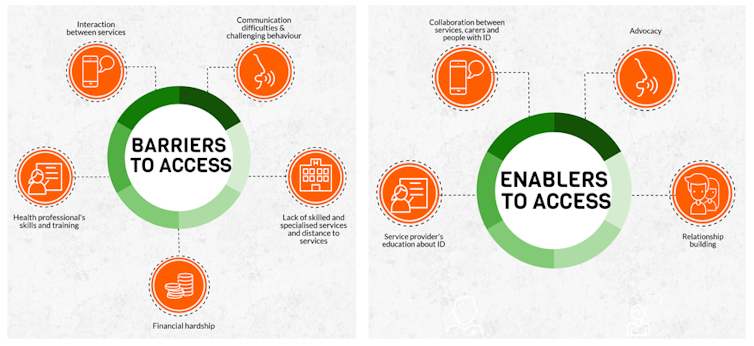

People with intellectual disability say many barriers stop them from getting the mental health and disability services they need. These can include living in locations that lack services. They can also be influenced by the way the NDIS and other services are organised. For instance, separating disability from other health services can mean people’s treatment is not coordinated, which can lead to poorer outcomes.

Barriers to access

Only a small number of NDIS and other services are available for many people with intellectual disability who need mental health support. The shortage of mental health services, especially in rural and regional Australia, affects the general population too.

People with intellectual disability often experience discrimination. from shutterstock.com

But the lack of accessible services is worse for people with intellectual disability. People speak about exhausting all the services in their area and being unable to travel a long way to get to a suitable service.

Attitudes also prevent people with intellectual disability and mental health receiving the few services that are available. People have shared stories about being excluded from services because of their intellectual disability or their mental health.

For instance, one parent told researchers that when the person they cared for tried to use a public mental health service, they were refused once the staff found out the person had an intellectual disability.

Staff in mental health services often do not have sufficient training on how to deal with intellectual disability. Similarly, staff in disability services do not have enough training about mental health. People’s mental health needs are often mis-identified, dismissed or not treated well even when they are identified.

In interviews, NDIS participants have told about times when their behaviours were unusual for them and a clear indication they were in mental distress, yet mental health staff dismissed the behaviour as part of their disability.

Read more: Five years on, NDIS is getting young people out of aged care, but all too slowly

Positive experiences

Some people with both intellectual disability and mental health needs have had positive experiences with the NDIS. These experiences show us what is needed to make access to services easier for people with complex needs.

We know what we need to do to make the NDIS experience equally satisfactory for everyone. Author provided

One of them is having a good advocate – a family, friend, formal advocate or service provider. It is important for service providers to listen to the advocate, especially when they know about the person’s ordinary behaviour and can identify when something is wrong.

Collaboration between the person and service is also important, as well as between mental health and disability services.

The NDIS has good examples of how to find the right services for people with complex needs. Support planners who have good communication and interpersonal skills can advocate for people and encourage self advocacy.

Some planners have disability themselves or have training from people with disability. People who have strong advocates have better outcomes in the NDIS so far.

The NDIS is striving to fulfill the rights of people with complex needs to benefit from the new services available through the scheme. Investing in specific training is crucial for planners, services, carers and people with intellectual disability.

Karen R Fisher, Professor, Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW; Erin Louise Whittle, PhD Candidate, UNSW, and Julian Norman Trollor, Professor, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.