A detailed commentary on this article is provided below ...

Autism diagnoses will be subject to the first nationally consistent set of standards to iron out “substantial” variability in medical approaches which has contributed to a dramatic increase in the number of people, especially children, being treated for the condition.

The number of people diagnosed with autism in Australia almost doubled between 2003 and 2006, and has doubled every three years since, to 115,000 in 2012. New data, when it is finalised, is expected to show that more than 230,000 have autism.

The $22 billion National Disability Insurance Scheme with the Co-operative Research Centre for Living with Autism — a conglomerate of institutions — commissioned a study which will inform new guidelines, led by University of Western Australia professor Andrew Whitehouse.

“It is highly likely that our inconsistent diagnosis standards have contributed to the growth in the numbers of kids diagnosed with autism,” Professor Whitehouse told The Australian.

“We have really strong evidence of variability in the way autism is diagnosed between clinicians, between states and between rural and metropolitan areas.

“This provides inequity — in waiting times, in the cost of the assessments — it is a huge gap in what people have access to.”

The set of behaviours that define autism are outlined in the internationally recognised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders but Professor Whitehouse said these inherently contained an “element of subjectivity”, which transferred to the way clinicians interpreted them for diagnosis.

Autism can be diagnosed in Australia using a “gold-standard” team of professionals — such as a pediatrician and psychologist — or by a single pediatrician, psychologist or psychiatrist.

“The bald fact is we do not always know what is going on around Australia,” Professor Whitehouse said.

“The variations are not just about who is doing the diagnosis, but how they are doing it.”

Research led by Professor Whitehouse earlier in the year revealed that some clinicians had admitted to diagnosing children who did not meet the criteria for autism or to using older versions of the DSM.

“We would not accept this state of affairs for any other condition and we should not accept it for autism,” he said.

The study, which will inform the first guidelines, will look at global best practice and include consultation with families and medical practitioners.

The NDIS, which will fund early intervention packages for children with developmental delays, has kept a keen eye on the space. The South Australian trial of the scheme was seriously delayed when the number of children eligible blew out by 100 per cent, almost entirely due to the number of children with autism.

Professor Whitehouse said the move to standardise diagnosis was not about “tightening the guidelines’’.

“This is about consistency, we must have consistency. We know that there are areas in Australia that can improve on this,” he said.

The Productivity Commission said it believed that a federal autism intervention program — Helping Children with Autism — was partly responsible for rising diagnosis rates.

from http://www.theaustralian.com.au/national-affairs/health/ndis-backs-stud…;

see also http://a4.org.au/node/1284

Commentary

Following is a paragraph by paragraph commentary on the article above by Bob Buckley.

Autism diagnoses will be subject to the first nationally consistent set of standards to iron out “substantial” variability in medical approaches which has contributed to a dramatic increase in the number of people, especially children, being treated for the condition.

This statement says that the internationally recognised DSM-5, and it predecessors, the DSM-IV and ICD-10, are/were not a "consistent set of standards".

I am not aware, and would be interested to see evidence, that "'substantial' variability in medical approaches has contributed to a dramatic increase in the number of people, especially children, being treated for [autism/ASD]". This claim is unsubstantiated and maybe inconsistent with the available evidence. The research literature shows a number of careful epidemiological studies of “autism” diagnosis but the results have not differed “substantially” from other credible but less rigorous approaches to indications of autism prevalence.

The number of people diagnosed with autism in Australia almost doubled between 2003 and 2006, and has doubled every three years since, to 115,000 in 2012. New data, when it is finalised, is expected to show that more than 230,000 have autism.

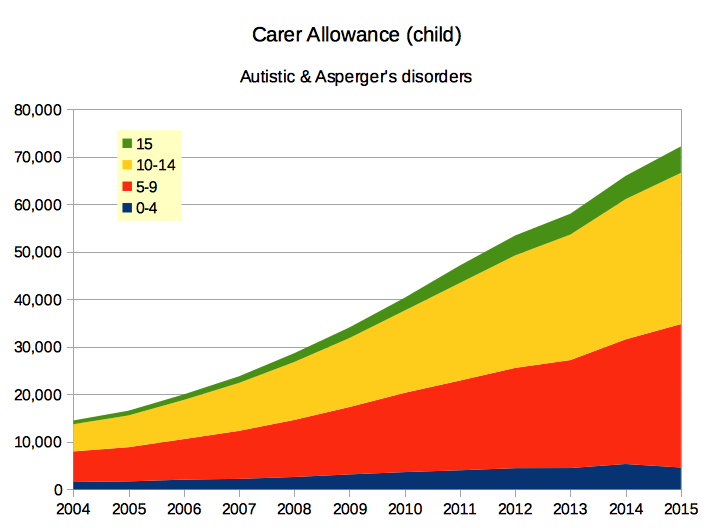

This paragraph appears to refer to estimates from the ABS Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC). But there was no data collected in 2006, the period was 2003 to 2009. Over the period, the number of people who said they have autism in Australia grew from 30,400 in 2003 to 64,400 in 2009 (see here) – that is 112% growth ... which is a bit more than "doubled" over the 6 year period. The numbers from this survey also doubled from 1998 to 2003. The 79% growth in numbers from 64,400 in 2009 to 115,400 in 2012 isn't really "doubled" (see here).

The mis-information above repeats previous errors (see Alarm at autism doctor shopping for diagnoses).

I predict that autism in the ABS's 2015 SDAC data, when the ABS releases its analysis, will fall well short of the 230,000 that the Australian has predicted repeatedly ... probably under 205,000. ABS SDAC data is neither the only nor the "best available" data on the number of ASD diagnoses in Australia.

Data suggest the number of Australians diagnosed with autism/ASD doubles every 5 years. And that increases in Australia are relatively consistent with growth in ASD numbers overseas ... over an extended period.

The $22 billion National Disability Insurance Scheme with the Co-operative Research Centre for Living with Autism — a conglomerate of institutions — commissioned a study which will inform new guidelines, led by University of Western Australia professor Andrew Whitehouse.

“It is highly likely that our inconsistent diagnosis standards have contributed to the growth in the numbers of kids diagnosed with autism,” Professor Whitehouse told The Australian.

The growing numbers of ASD diagnoses is an international phenomenon. Revision/updating of the diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5 (published in 2013) was meant to tighten up criteria for ASD. Most experts agreed that the DSM-5 did tighten diagnostic criteria.

Despite inconsistent diagnosis standards between countries, the result is similar prevalence and growth. It's a remarkable phenomenon all down to coincidence.

It seems that Prof Whitehouse and his colleagues regard the changes in the DSM-5 as having failed. Apparently, they expect to devise better guidelines.

“We have really strong evidence of variability in the way autism is diagnosed between clinicians, between states and between rural and metropolitan areas.

“This provides inequity — in waiting times, in the cost of the assessments — it is a huge gap in what people have access to.”

While Prof. Whitehouse may have some "evidence of variability in the way autism is diagnosed between clinicians, between states", the significance of the variance is very unclear. Many parents need to see multiple clinicians before they find one who believes autism even exists. The variability between states suggests that there may be state-based diagnosis cultures. Note: the variation between states in the US is more pronounced than in Australia.

One crucial aspect is that the ABS SDAC data shows that even with a 79% increase in diagnosis numbers, most autistic people 73% have severe or profound disability. Employment and education outcomes, especially tertiary education, remain abysmal. If the increase were due substantially to inappropriate or much milder cases, which seems to be Prof Whitehouse's concern, then these outcomes would improve significantly. Or is there some other explanation for these measures?

Currently, just 30% of autistic children are diagnosed by age 6 years, the latest that the federal government allows autistic children into its "early intervention" schemes. This is an abysmal result.

I support improving diagnoses provided

-

there is evidence of substantial mis-diagnosis in the current system

-

the changes tackle both under-diagnosis and over-diagnosis proportionally, and

-

the changes ensure diagnosis is quicker and cheaper.

But it is very likely that Prof. Whitehouse's diagnosis guidelines, should they be adopted, will cause further delays and cost to ASD diagnosis.

Prof Whitehouse mention variability between states: the ASD diagnosis rate in Western Australia, where Prof Whitehouse comes from, is half the national average. His home state, Western Australia, is a clear anomaly: only the Northern Territory has a lower diagnosis rate than Western Australia.

At the same time, the NDIA now promotes its view that children don't even need an ASD diagnosis (ref ???); instead the NDIA promotes generic early intervention for autistic children that is cheaper but does not have an evidence base for autistic children. The likely consequence of the NDIA’s ECEI Approach is that autistic children will get substantially reduced benefit from their early intervention and the long-term cost of the NDIA’s ECEI Approach for autistic children will be substantial in both human and economic terms.

The set of behaviours that define autism are outlined in the internationally recognised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders but Professor Whitehouse said these inherently contained an “element of subjectivity”, which transferred to the way clinicians interpreted them for diagnosis.

Autism can be diagnosed in Australia using a “gold-standard” team of professionals — such as a pediatrician and psychologist — or by a single pediatrician, psychologist or psychiatrist.

“The bald fact is we do not always know what is going on around Australia,” Professor Whitehouse said.

“The variations are not just about who is doing the diagnosis, but how they are doing it.”

Research led by Professor Whitehouse earlier in the year revealed that some clinicians had admitted to diagnosing children who did not meet the criteria for autism or to using older versions of the DSM.

The NDIA was very keen to see the report say "some clinicians had admitted to diagnosing children who did not meet the criteria for autism". However, this seems to be something of an exaggeration of the finding. The actual findings were not spelled out clearly in the report. It turns out that 2.04% of clinicians say they sometimes give an ASD diagnosis when a child doesn't meet the diagnostic criteria. Some fraction of 2.04% is a very small "some". It is likely that this is well under Australia's mis-diagnosis rate for ASD (though no one provides an estimate of that).

The report does not tell us how many clinicians may have not diagnosed ASD when symptoms were present. There are very credible reports of high numbers of families needing to follow through on multiple referrals to get their child diagnosed with ASD.

The report ignores the likely prospect of substantial initial under-diagnosis of ASD … there is no discernible attempt to see how many clinicians may have not given a diagnosis when a child met most or all of the criteria for ASD. It is highly likely that when "some clinicians had admitted to diagnosing children who did not meet the criteria for autism", some or all of those clinicians were wrong and the child did in fact meet the criteria.

It is disappointing that the research behind the Autism CRC’s report may have a strong bias towards finding and reporting over-diagnosis.

The Autism CRC, in its report, apparently did not investigate policy influences on ASD diagnoses. In South Australia, the Government paid for a diagnosis of Autistic or Asperger’sDisorder but did not pay for a diagnosis of PDD-NOS. The same applies to Carer Allowance (child). The Medicare item brought in in 2008 only pays for a successful diagnosis of autism; clinicians cannot claim for the (often substantial) work they put into saying “no, not ASD”. Policies such as these may affect diagnosis decisions in marginal cases.

“We would not accept this state of affairs for any other condition and we should not accept it for autism,” he said.

There are plenty of "conditions" with acceptable mis-diagnosis rates that are well over some fraction of 2.04%. Prof Whitehouse seems to be exaggerating the significance.

The study, which will inform the first guidelines, will look at global best practice and include consultation with families and medical practitioners.

The NDIS, which will fund early intervention packages for children with developmental delays, has kept a keen eye on the space. The South Australian trial of the scheme was seriously delayed when the number of children eligible blew out by 100 per cent, almost entirely due to the number of children with autism.

There was no “blow out” in South Australia. The miscalculation was due entirely to the state and federal governments, and the NDIA, refusing to listen to advice and completely ignoring the available data on the number autistic children in South Australia. This is not a diagnosis issue ... its an example of the NDIA's refusal to engage with the ASD community (except people who promise research that backs the NDIA’s prejudice against autism).

Professor Whitehouse said the move to standardise diagnosis was not about “tightening the guidelines’’.

It is impossible to “standardise diagnosis” or to introduce guidelines where none currently existed without “tightening the guidelines”. Any more rigorous standard will certainly cause delay and increase cost.

“This is about consistency, we must have consistency. We know that there are areas in Australia that can improve on this,” he said.

Given that autism is a spectrum, Prof Whitehouse should explain what he means by "consistency" and what problems there are. It may be unrealistic to expect rigorous consistency when dealing with this “spectrum”.

The existing data suggests that ASD diagnosis rates in Western Australia need improving. Surely Prof Whitehouse and his collaborators should first work on getting diagnosis in WA up to the national standard, before complaining like this.

There seems to be increasing difficulty getting WA clinicians to comply with reporting requirements of the WA’s Autism Registry (see http://www.autismwa.org.au/2014%20report_draft_final_16.7.15.pdf). Their 2014 Annual Report shows case notifications dropping since 2008 … it says “The decrease in the number of people registered since 2008 is considered to be a reflection of decreased case notification rather than a decrease in the actual rates of diagnosis.” Note that 450 new cases in WA in 2008 is still well below the number of new cases of Carer Allowance (child) due to autism in WA … so the WA Autism Registry may never accurately shown autism incidence or prevalence in WA.

The Productivity Commission said it believed that a federal autism intervention program — Helping Children with Autism — was partly responsible for rising diagnosis rates.

The Productivity Commission did not explain how the Helping Children with Autism (HCWA) package caused a world-wide increase in autism diagnoses that started well before HCWA was even conceived. If HCWA played a part, the part is so small it is not even visible in Australian data.