It took Mariam Mukhtar nearly two years to have her teenage son Raamiz assessed for autism following a paediatric referral, and she fears the delay in getting him support has cost him his high school experience.

“Having support at the right time … that would have been a life-changing experience,” she said.

Raamiz showed early signs of developmental delays, but the year 9 student’s symptoms were amplified when he started high school. Raamiz didn’t understand social cues, constantly forgot his books, was hyperactive in class and struggled academically.

It took more than 18 months for Mariam’s 14-year-old son Raamiz to be seen by a specialist to diagnose him. Her younger son Wadi Hassan (pictured) also has autism, but was diagnosed early and has access to support.CREDIT:DION GEORGOPOULOS

After some difficult juggling to collect school and behavioural reports, Raamiz received a paediatric referral to the Children’s Hospital at Westmead for assessment.

Raamiz was 13 when he received the referral, but it wasn’t until last month – a few weeks shy of his 15th birthday – that the assessment took place.

He was diagnosed with level 2 autism spectrum disorder, which requires “substantial” support, anxiety and ADHD, and has been recommended speech therapy, occupational therapy and psychology.

The diagnosis and report mean Raamiz can receive funding for support at school and will have a smoother transition onto the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

“His teachers have told me if they had known about [his diagnosis] from the beginning, they would have worked more with him. If he had got support, he wouldn’t be struggling now,” Mukhtar said.

Professor Adam Guastella, the Michael Crouch chair for child and youth mental health at the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre in Westmead, analysed service wait time through the Sydney child neurodevelopment registry.

“It’s very common for families to be waiting two years in Sydney, and that can be longer in rural and regional areas,” he said.

Neurodevelopmental assessments often involve paediatricians, speech therapists, occupational therapists and psychologists and require a referral from a paediatrician.

Guastella said there had been a “surge in demand” for neurodevelopmental assessments across the past several years as the community became more aware of disorders such as autism.

“There’s demand that’s been increasing year-on-year for these services, and that’s affecting everyone, but especially those in the public system where, if you don’t have finance, that’s your only option,” he said.

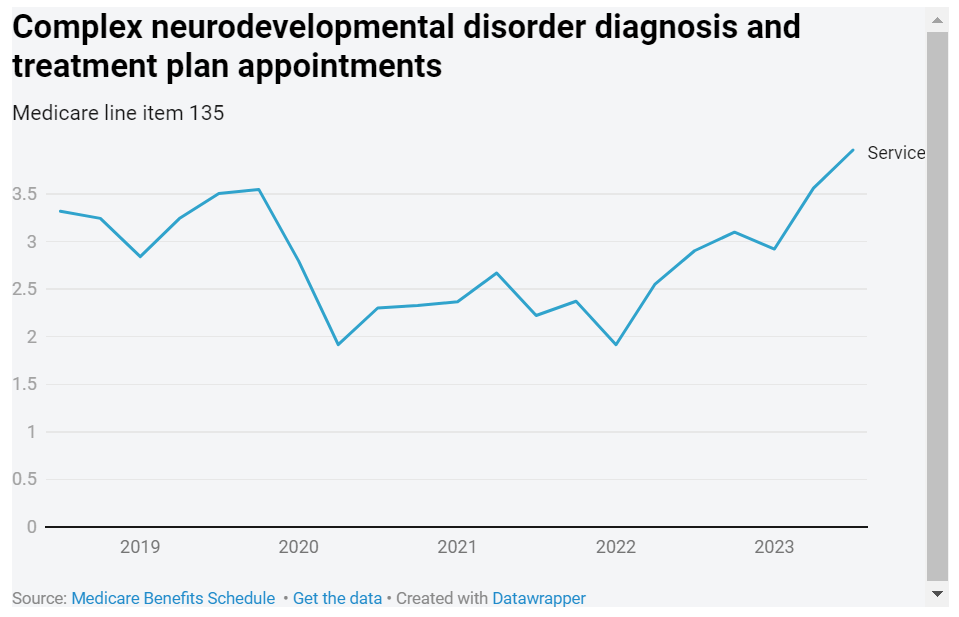

Medicare data shows the number of people aged under 25 who saw a Medicare-funded paediatrician for a diagnosis or treatment plan for a complex neurodevelopmental disorder, including autism, hit record highs in the October quarter, with nearly 4000 appointments – a 17 per cent increase on the same quarter five years ago.

These appointments can only be accessed once per lifetime.

A February study, co-authored by Guastella, found 88 per cent of caregivers who attended the child development unit at the Children’s Hospital at Westmead, which typically deals with more complex cases, knew their child needed support by school age, but just half of them had it when school began.

The average age caregivers identified developmental concerns was three, but the average age of receiving a developmental assessment was 6.6 years, the study found.

A NSW Health spokesperson said the unit now had an average wait time of seven months for children under four, and 18 months for children aged four to 16.

Guastella said that along with increasing the workforce capacity, more interventions should be made available for families that do not require a diagnosis.

Autism Australia chief executive Nicole Rogerson said the issue was “catastrophic”.

“Any delay in having a child assessed for a developmental delay and getting them into effective early intervention has a catastrophic effect on their lives,” she said.

Children with autism often have delayed communication and social skills, and early intervention can help close the gap between them and their typically developing peers, she said.

“The delay has this flow-on effect down the road in education, in health, and whether they need NDIS funding,” she said.

“We shouldn’t be playing that kind of lottery when talking about little toddlers.”

More than half of NDIS participants under 18 years old have an autism diagnosis, and more than 8 per cent of five- to seven-year-olds are now on the scheme.

NDIS Minister Bill Shorten has flagged he will tighten access to the scheme for those with autism to address the scheme’s cost blowouts.

GP and member of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners ADHD, ASD and Neurodiversity Specific Interest group Dr Melita Cullen said she was particularly concerned about the delays in getting older children diagnosed.

While children under nine years old who show signs of developmental delays can access support via the NDIS’ early childhood pathway without an official diagnosis, older children can’t.

Children with ADHD also can’t start stimulant medication until they see a paediatrician, which can take years in some areas, she said.

“Kids with undiagnosed autism or ADHD can be treated punitively by schools, which may lead to anxiety or depression,” she said.

A spokesperson for NSW Health said child development services is a “whole of sector” responsibility shared by the public health system, private providers, primary care and funded non-government organisations.

“Clinics continue to experience significant and sustained demand due to the level of new referrals being received. New referrals are triaged and prioritised based on urgency and acute clinical need,” the spokesperson said.